IPC, Pipes and Sockets

Agenda

- Communication between processes and across the world looks like File I/O

- Introduce Pipes and Sockets

- Introduce TCP/IP Connection setup for Webserver

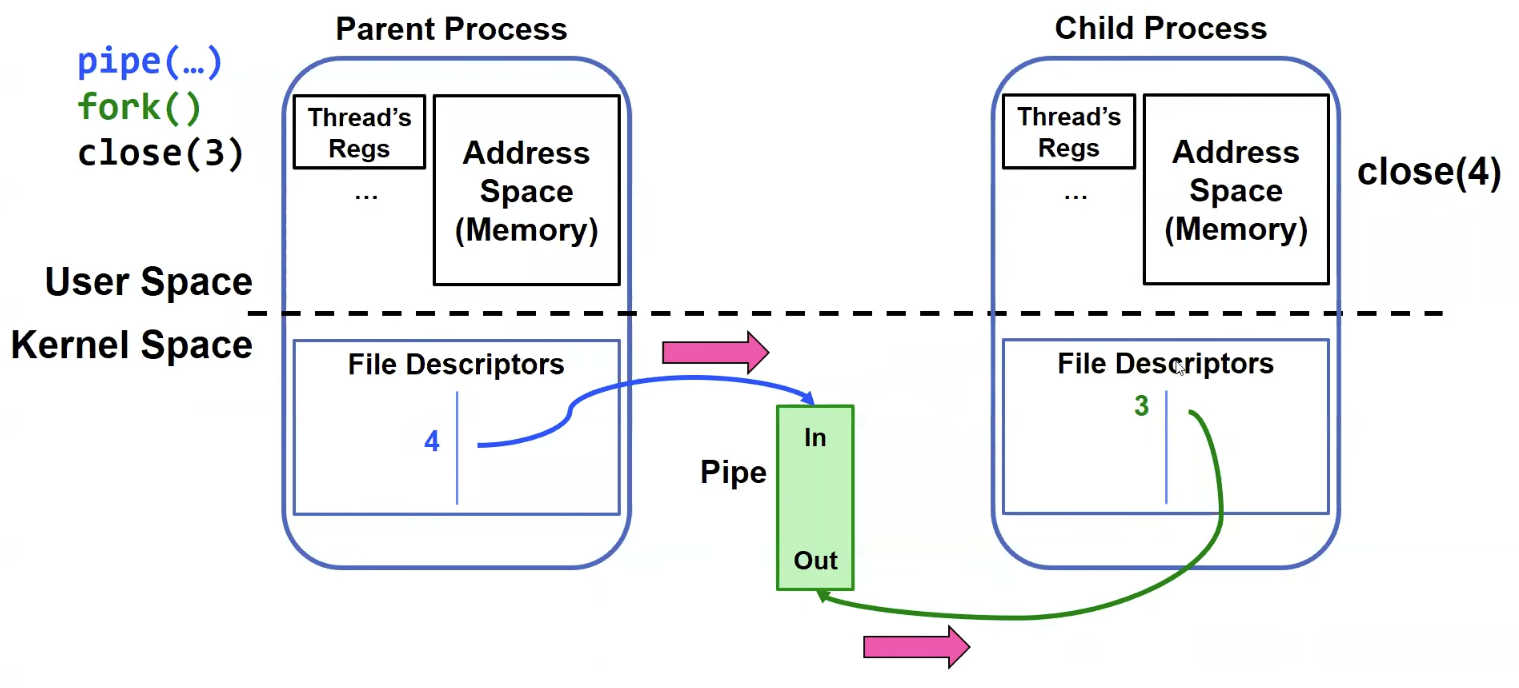

Pipes

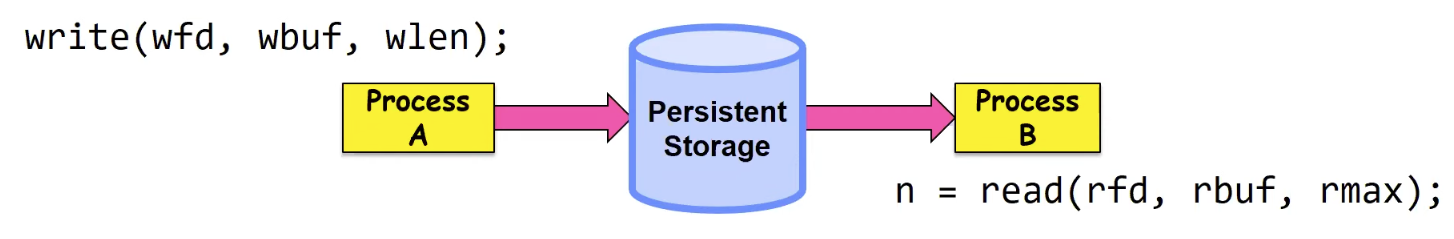

As we have seen in the last lecture, two processes can share file descriptions, meaning they can communicate through a file.

However, this is slow and very expensive because those processes are located in memory they don’t have to go to disk to communicate. Another reason this is not desirable is because we cannot establish persistent connection using files between two processes.

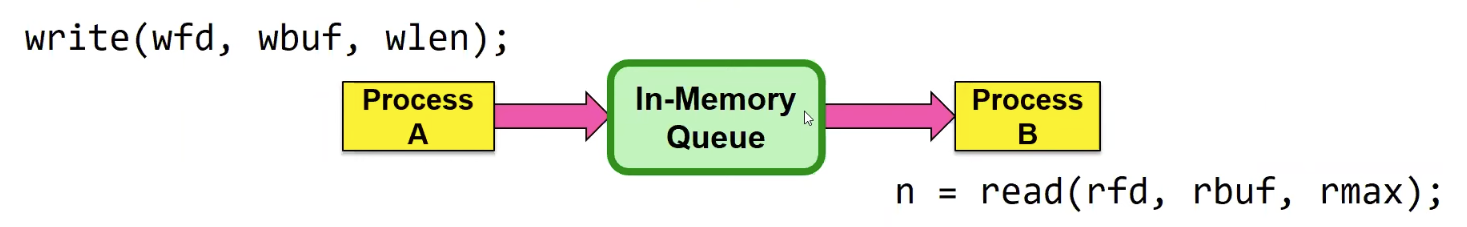

A more efficient way would be using an In-Memory Queue

Data written by A is held in memory until B reads it. We access the queen using system calls (for security reasons). It’s the same interface as we use for files. However, there are some questions:

- What if A generates data faster than B can consume it?

- What if B generates data faster than A can product it?

The way we solve synchronization problem is by waiting. When A executes a write system call, but the queue is full we want A to go to sleep. When B executes a read system call, but the queue is empty, we want to put B to sleep.

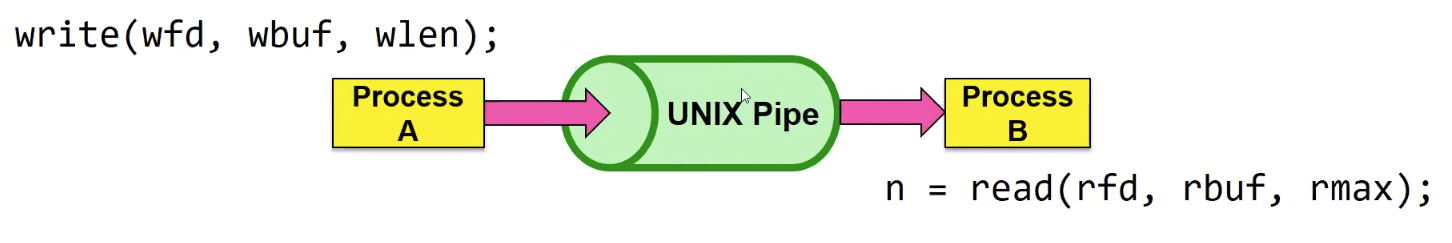

In UNIX, A pipe is just a memory queue/buffer in the kernel. The memory buffer is finite:

- If producer(

A) tries to write when buffer is full, itblocks(put sleep until space) - If producer(

B) tries to read when buffer is empty, itblocks(put sleep until data)

int pipe(int fd[2])l

- Allocates two new file descriptors in the process

- Writes to `fd[1]`, read from `fd[0]`

- Implemented as a fixed-size queue

Here is an example of how to write and read data from pipe:

#include <unistd.h>

#define BUFSIZE 1024

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

char *msg = "Message in a pipe.\n";

char buf[BUFSIZE];

int pipe_fd[2];

if (pipe(pipe_fd)) {

fprintf (stderr, "Pipe failed.\n"); return EXIT_FAILURE;

}

// The write calls from user space into the kernel

ssize_t writelen = write(pipe_fd[1], msg, strlen(msg)+1);

printf("Sent: %s [%ld, %ld]\n", msg, strlen(msg)+1, writelen);

ssize_t readlen = read(pipe_fd[0], buf, BUFSIZE);

printf("Rcvd: %s [%ld]\n", msg, readlen);

close(pipe_fd[0]);

close(pipe_fd[1]);

exit(0);

}

The code above runs in a single process. To following example demonstrates how two process communicate using a pipe:

int main() {

pid_t pid = fork();

if (pid < 0) {

fprintf (stderr, "Fork failed.\n");

return EXIT_FAILURE;

}

if (pid != 0) {

// the parent process

close(pipe_fd[0]); // close the read end

ssize_t writelen = write(pipe_fd[1], msg, msglen);

printf("Parent: %s [%ld, %ld]\n", msg, msglen, writelen);

} else {

// child process

close(pipe_fd[1]); // close the write end

ssize_t readlen = read(pipe_fd[0], buf, BUFSIZE);

printf("Child Rcvd: %s [%ld]\n", msg, readlen);

}

exit(0)

}

To send data from the child process to the parent process, we can do the opposite way. The child process will close the read-end and the parent process will close the write-end.

When do we get EOF on a pipe?

- After last “write” descriptor is closed, pipe is effectively closed:

read()returns onlyEOF

- After last “read” descriptor is closed, writes generate

SIGPIPEsignals:- If processes ignores, then the

write()fails with aEPIPEerror

- If processes ignores, then the

We need a protocol

- A protocol is an agreement on how to communicate

- Syntax: how a communication is specified and structured

- package format, order message are sent and received

- Semantics: what a communication means

- actions taken when transmitting, receiving, or when a timer expires

- Syntax: how a communication is specified and structured

- Described formally by a state machine

- Often represented as a message translation diagram

- In fact, across network may need a way to translate between different representations for numbers, strings, etc.

- Such translation typically part of a Remote Procedure Call (RPC) facility

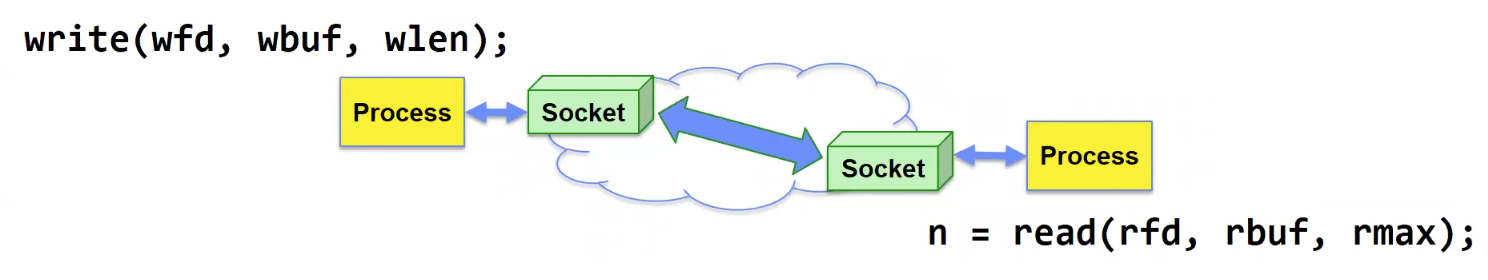

The Socket Abstraction

- Socket: an abstraction of a network I/O queue (Endpoint for Communication)

- Queues to temporarily hold results

– Another mechanism for inter-process communication

– Embodies one side of a communication channel

- Same interface regardless of location of other end

- Could be local machine (called “UNIX socket”) or remote machine(called “network socket”) – First introduced in 4.2 BSD UNIX

- Now most operating systems provide some notion of socket

- Queues to temporarily hold results

– Another mechanism for inter-process communication

– Embodies one side of a communication channel

- Data transfer like files

- Read / Write against a descriptor

- Same abstraction for any kind of network

- Local to a machine

- Over the internet (TCP/IP, UDP/IP)

- Things no one uses anymore (OSI, Appletalk, SNA, IPX, SIP, NS, …)

Sockets in detail

- Looks just like a file with a file descriptor

- Corresponds to network connection (two queues)

writeadds to output queue (queue of data destined for other side)readremoves from it input queue(queue of data destined for this side)- Some operations do not work, e.g.

lseek

- How can we use sockets to support real applications

- A bidirectional byte stream isn’t useful on its own

- May need messaging facility to partition stream into chunks

- May need RPC facility to translate one environment to another and provide the abstraction of a function call over the network

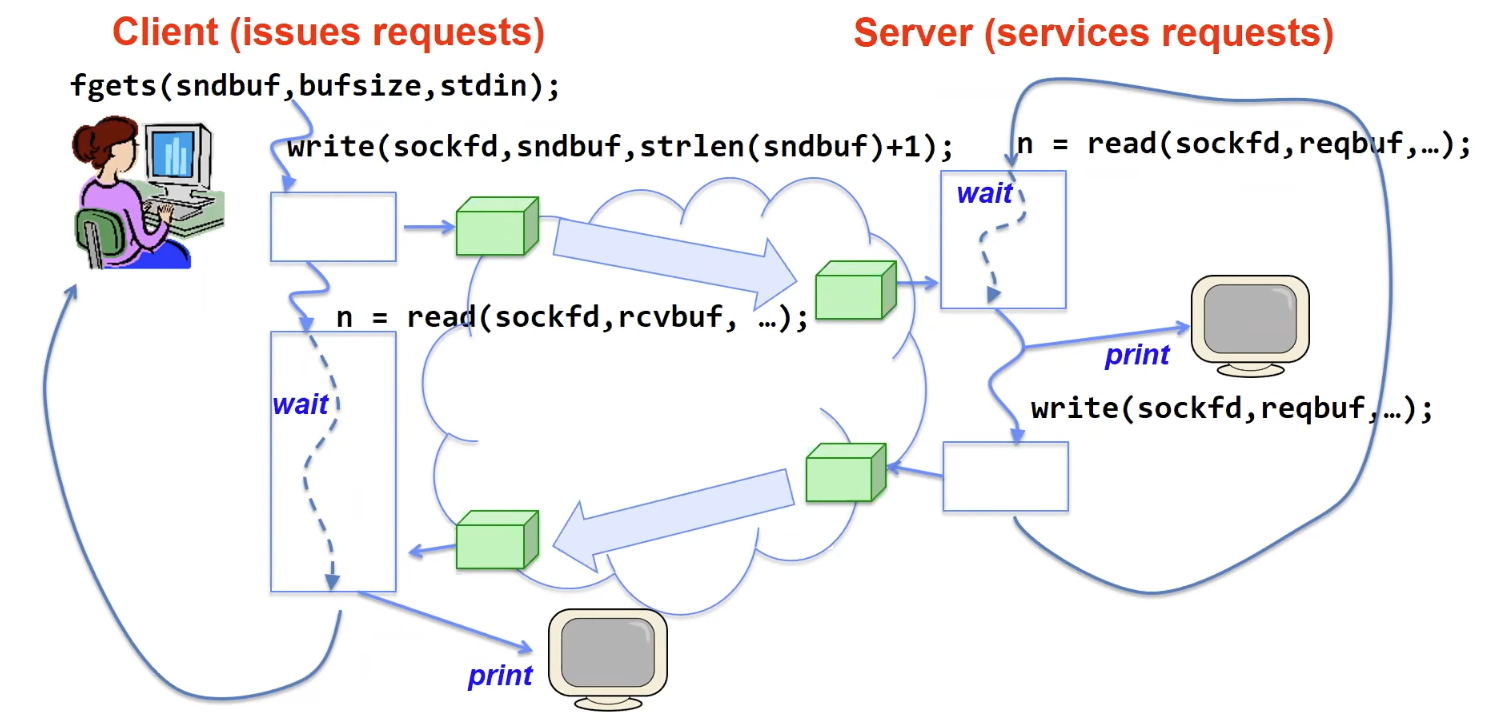

Simple Example: Echo Server

- We have two sockets - one on the client side and one on the server side

- The green boxes are sockets buffer inside the kernel

- The white boxes are users level code that interact with the kernel

// client side code

void client(int sockfd) {

int n;

char sndbuf[MAXIN]; char rcvbuf[MAXOUT];

getreq(sndbuf, MAXIN); /* prompt */

while (1) {

write(sockfd, sndbuf, strlen(sndbuf)); /* send */

memset(rcvbuf,0,MAXOUT); /* clear */

n=read(sockfd, rcvbuf, MAXOUT‐1); /* receive */

write(STDOUT_FILENO, rcvbuf, n); /* echo */

getreq(sndbuf, MAXIN); /* prompt */

}

}

// server side code

void server(int consockfd) {

char reqbuf[MAXREQ];

int n;

while (1) {

memset(reqbuf,0, MAXREQ);

n = read(consockfd,reqbuf,MAXREQ‐1); /* Recv */

if (n <= 0) return;

n = write(STDOUT_FILENO, reqbuf, strlen(reqbuf));

n = write(consockfd, reqbuf, strlen(reqbuf)); /* echo*/

}

}

What assumptions are we making here?

- Reliable

- Write to a file => Read it back. Nothing is lost.

- Write to a (TCP) socket => Read from the other side, same.

- Like pipes

- In order (sequential stream)

- Write X then write Y => read gets X then read gets Y

- When ready?

- File read gets whatever is there at the time.

- Assumes writing already took place.

- Blocks if nothing has arrived yet

- Like pipes!

Sockets Creation

- File systems provide a collection of permanent objects in structured name space

- Processes open, read/write/close them

- Files exist independent of the processes

- Easy to name what file to

open()

- Pipes: one-way communication between processes on the same physical machine

- Single queue

- Created transiently by a call to

pipe() - Passed from parent to children(descriptors inherited from parent process)

- Sockets provide a two-way communication between processes on same or different machines

- Two queues (one in each direction)

- Processes can be on separate machines

Namespaces for communication over IP

- Hostname

www.eecs.berkeley.edu

- IP address

128.32.244.172(IPv4, 32bit integer)2067:f140:0:81::f(IPv6, 128bit integer)

- Port Number

0-1023are “well known” or “system” ports- Superuser privileges to bind to one

1024 - 49151are “registered” ports (registry)- Assigned by IANA for specific services

49152-65535(2^15+2^14to2^16-1) are “dynamic” or “private”- Automatically allocated as “ephemeral Ports”

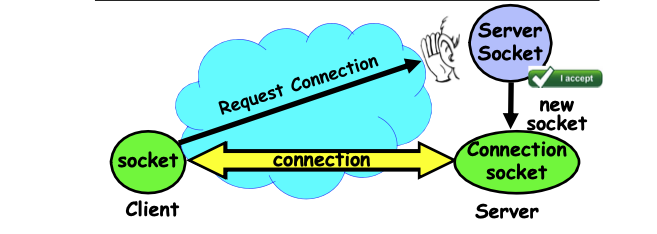

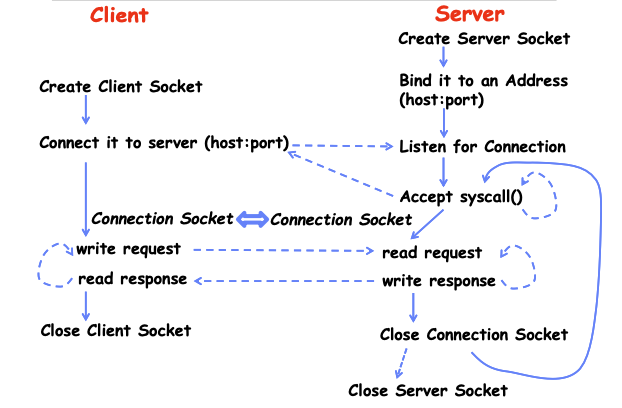

Connection Setup over TCP/IP

- Special kind of socket: server socket

- Listens for new connections

- Produces new sockets for each unique connection

- 3-way handshake to establish new connection (TCP/IP)

- Two operations:

listen(): Start allowing clients to connectaccept(): Create a new socket for a particular client connection

- Things to remember

-

5 Tuple identifies each connection</mark> - source IP address (Client Addr)

- source Port number(Client Port)

- destination IP Address (Server Addr)

- destination port number(Server Port)

- Protocol (always TCP here)

- Often, Client Port is “randomly” assigned

- Done by OS during client socket setup

- Server Port often “well known”

80(web),443(secure web),25(sendmail), etc- Well-known ports from

0—1023

-

Sockets in concept

- client protocol

char *host_name, port_name;

// Create a socket

struct addrinfo *server = lookup_host(host_name, port_name);

int sock_fd = socket(server‐>ai_family, server‐>ai_socktype, server‐>ai_protocol);

// Connect to specified host and port

connect(sock_fd, server‐>ai_addr, server‐>ai_addrlen);

// Carry out Client‐Server protocol

run_client(sock_fd);

/* Clean up on termination */

close(sock_fd);

// getting the server addresss

struct addrinfo *lookup_host(char *host_name, char *port) {

struct addrinfo *server;

struct addrinfo hints;

memset(&hints, 0, sizeof(hints));

hints.ai_family = AF_UNSPEC;

hints.ai_socktype = SOCK_STREAM;

int rv = getaddrinfo(host_name, port_name, &hints, &server);

if (rv != 0) {

printf("getaddrinfo failed: %s\n", gai_strerror(rv));

return NULL;

}

return server

}

- server protocol (v1)

// Create socket to listen for client connections

char *port_name;

struct addrinfo *server = setup_address(port_name);

int server_socket = socket(server‐>ai_family,

server‐>ai_socktype, server‐>ai_protocol);

// Bind socket to specific port

bind(server_socket, server‐>ai_addr, server‐>ai_addrlen);

// Start listening for new client connections

listen(server_socket, MAX_QUEUE);

while (1) {

// Accept a new client connection, obtaining a new socket

int conn_socket = accept(server_socket, NULL, NULL);

serve_client(conn_socket);

close(conn_socket);

}

close(server_socket);

// server addresss - itself

struct addrinfo *setup_address(char *port) {

struct addrinfo *server;

struct addrinfo hints;

memset(&hints, 0, sizeof(hints));

hints.ai_family = AF_UNSPEC;

hints.ai_socktype = SOCK_STREAM;

hints.ai_flags = AI_PASSIVE;

getaddrinfo(NULL, port, &hints, &server);

return server;

}

The v1 implementation can only handle one connection at a time. It close the socket after accepting/processing the client-side request.

- server protocol (v2)

// Start listening for new client connections

listen(server_socket, MAX_QUEUE);

while (1) {

// Accept a new client connection, obtaining a new socket

int conn_socket = accept(server_socket, NULL, NULL);

pid_t pid = fork(); // New process for connection

if (pid == 0) { // Child process

close(server_socket); // Doesn’t need server_socket

serve_client(conn_socket); // Serve up content to client

close(conn_socket); // Done with client!

exit(EXIT_SUCCESS);

} else { // Parent process

close(conn_socket); // Don’t need client socket

wait(NULL); // Wait for our (one) child

}

}

close(server_socket);

In the v2 implementation, once we receive the client-side request, we fork a child process to process the request. Since the child process is just a duplicate of the parent process, it has both sockets. However, the child process only cares about the connect_socket, so it just close the server_socket. Likewise, the parent process does not care how the request is being processed, so once a connection is established, it just discards the conn_socket and wait for the child process to finish.

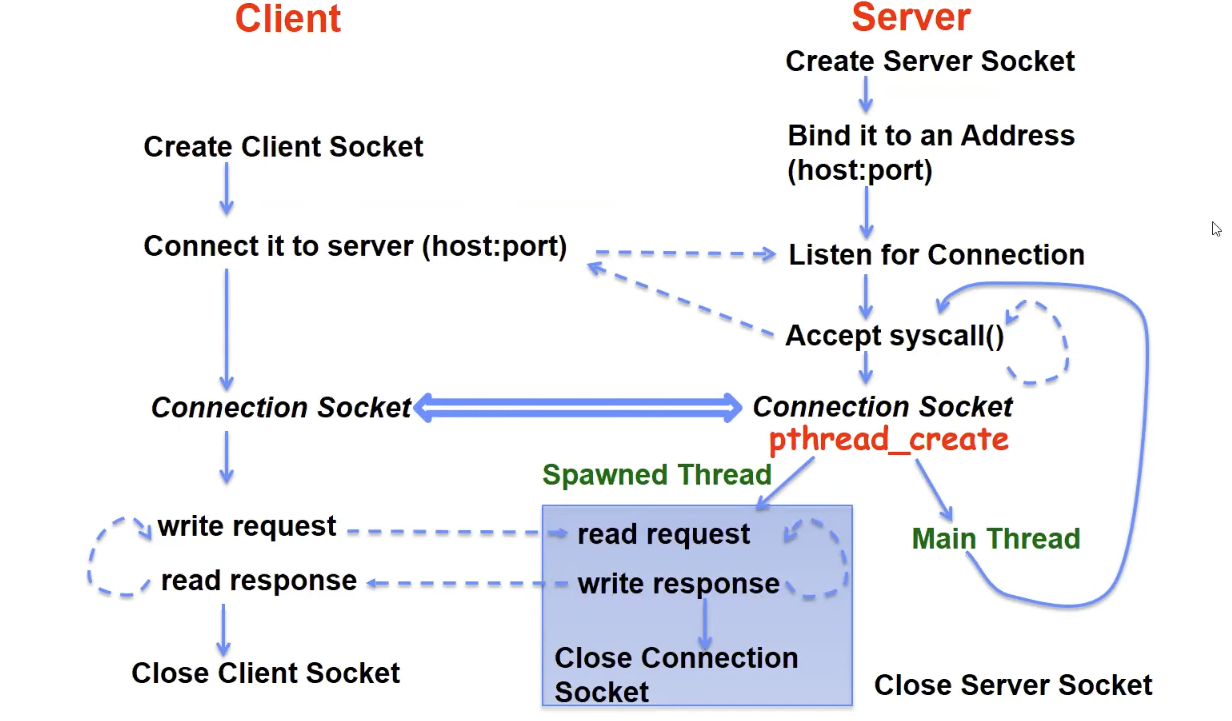

Concurrent Server

So far, our server implementation listens and queues requests, and it waits for each connection to terminate before initiating the next.

A concurrent server can handle and service a new connection before the previous client disconnects. We don’t need to wait for the previous connection to finish.

// Start listening for new client connections

listen(server_socket, MAX_QUEUE);

signal(SIGCHLD,SIG_IGN); // Prevent zombie children

while (1) {

// Accept a new client connection, obtaining a new socket

int conn_socket = accept(server_socket, NULL, NULL);

pid_t pid = fork(); // New process for connection

if (pid == 0) { // Child process

close(server_socket); // Doesn’t need server_socket

serve_client(conn_socket); // Serve up content to client

close(conn_socket); // Done with client!

exit(EXIT_SUCCESS);

} else { // Parent process

close(conn_socket); // Don’t need client socket

// wait(NULL); // Don’t wait (SIGCHLD ignored, above)

}

}

close(server_socket);

The only difference from the v2 implementation is wait(NULL) has been commented out. The parent process is only doing the listening work. The child process is responsible for communicating with the client. So the parent keeps accepting new connections, each child gets a different socket connection. Every loop gets a new child process for a new request.

Although we’ve achieved concurrency, forking processes is quite expensive. A lighter-weight approach is to use threads

- Here we spawn a new thread to handle each connection.

- The main thread initiates new client connections without waiting for previously spawned threads to finish

- Why give up the protection of separate processes (aka

fork)?- More efficient to create new threads than processes

- More efficient to switch between threads

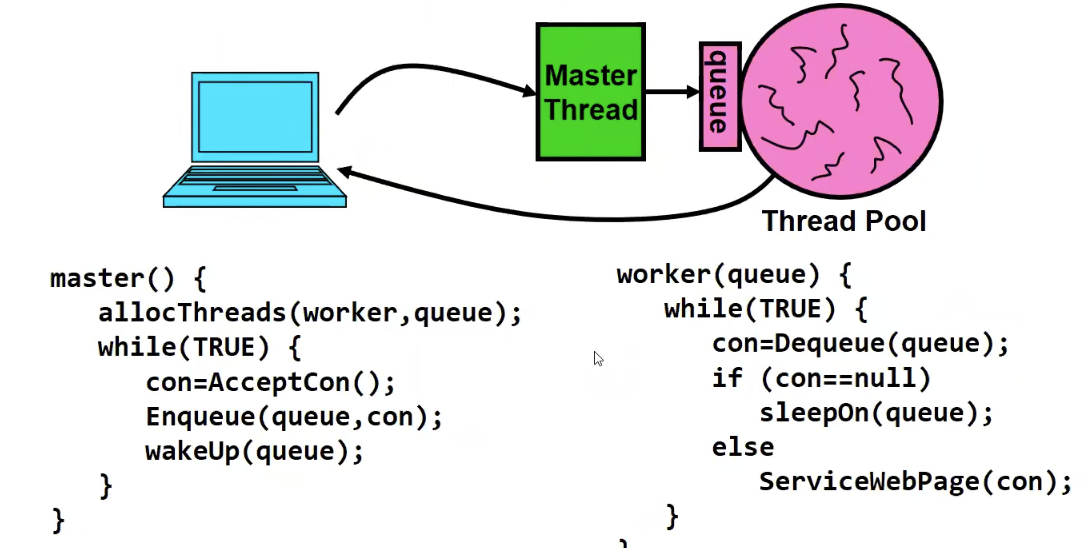

Thread Pool

However, when there are too many incoming requests, we will spawn too many threads, which will likely to crash the kernels. Thus, we need a thread pool to manage the creation of threads.

The idea is that we create a bunch of threads in the beginning, but it’s a fixed number. And every time an incoming request comes in we put the connection on an incoming queue (enqueue), and when a thread becomes free, it just dequeues the next connection and handles it.

Summary

- Interprocess Communication(IPC)

- Communication facility between protected environments(i.e. processes)

- Pipes are an abstraction of a single queue

- One end write-only, another and read-only

- Used for communication between multiple processes on one machine

- File descriptors obtained via inheritance

- Sockets are an abstraction of two queues, one in each direction

- Can read and write to either end

- Used for communication between multiple processes on different machines

- File descriptors obtained via socket/bind/connect/listen/accept

- Inheritance of file descriptors on fork() facilities

- Both support

read/writesystem calls, just like File I/O

Resources

Appendix: A web server

Processes communication sequences across user and kernel space when dealing with networking request in a web server.