Concurrency and Mutual Exclusion

Agenda

- Processes Multiplexing

- How does the OS provide concurrency through threads

- Brief discussion of process/thread states and scheduling

- High-level discussion of how stacks contribute to concurrency

- Introduce needs for synchronization

- Discussion of Locks and Semaphores

Definitions

- Synchronization: Using atomic operations to ensure cooperation between threads

- Mutual Exclusion: Ensuring that only one thread does a particular thing at a time

- Critical Section: A piece of code that only one thread can execute at once. Only one thread at a time will get into this section of code

- Critical section is the result of mutual exclusion

- Critical section and mutual exclusion are two ways of describing the same thing

Processes Multiplexing

The Process Control Block(PCB)

- A chunk of memory in the Kernel represents each process as a process control block (PCB)

- Status (running, ready, blocked, …)

- Register state (when not running)

- Process ID (PID), User, Executable, Priority, …

- Execution time, …

- Memory space, translation, …

- Kernel Scheduler maintains a data structure containing the PCBs

- Give out CPU to different processes (who gets the CPU to run themselves!)

- This is a Policy Decision

- Give out non-CPU resources

- Memory/IO

- Another policy decision

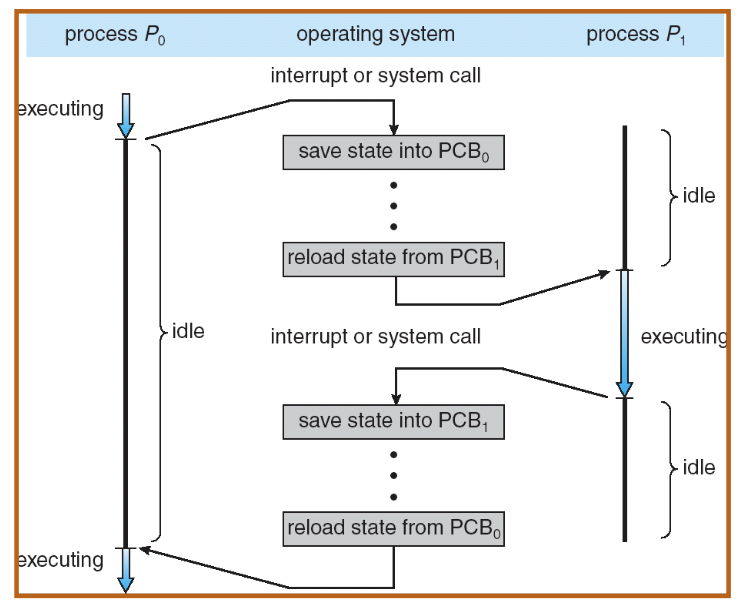

Context Switch

We use a single thread process as an illustration of how context switching work between two processes

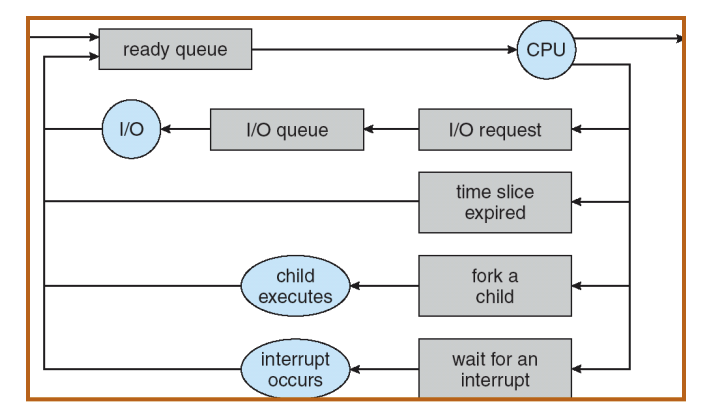

Scheduling: All About Queues

If we look inside the kernels, we have a ready queue for processes that are pending for execution. We also have a run queue for CPU. There are many other queues as well. What happens here is the PCB works their way from the ready queue to CPU. Scheduling is about deciding which process in the ready queue gets the CPU next. For example, when fork happens, the child process will be put into the ready queue waiting for CPU cycles.

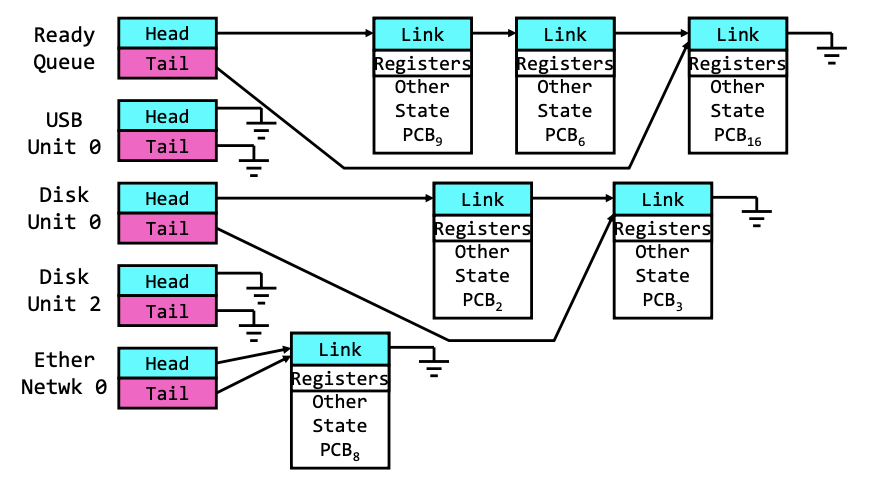

Ready Queue And Various I/O Device Queues

We have a lot of queues in the system. For each queue, it is structured as a linked list. They all have suspended processes in them. The scheduler is only interacting with the ready queue. The rest of the queue are interacted with the device drivers. For example, in the disk queue, once a process finishes the operation, it’ll remove its PCB from the queue, and put it back to the ready queue.

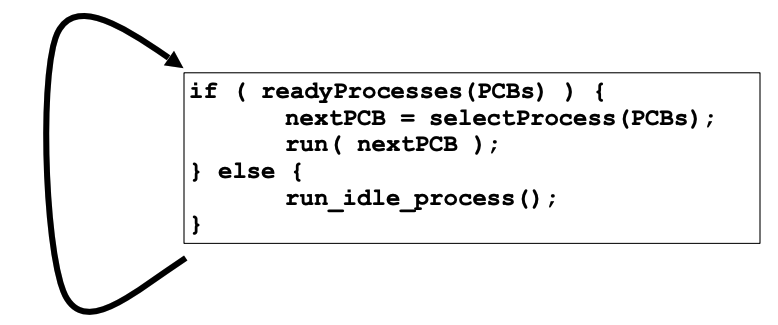

The core of Concurrency: the Dispatch Loop

The scheduler is a simple loop

- Scheduling: Mechanism for deciding which processes/threads receive the CPU

- Lots of different scheduling policies provide – Fairness or Real-time guarantees or Latency optimization or…

Conceptually, the scheduling loop of the operating system looks as follows

// an inifinte loop

Loop {

RunThread();

ChooseNextThread();

SaveStateOfCPU(curTCB); // TCB: thread control block

LoadStateofCPU(newTCB);

}

Running a thread

- How do I run a thread?

- Load its state (registers, PC, stack pointer) into CPU

- Load environment (virtual memory space, etc.)

- Jump to the PC and start running

One thing to note is that both OS (which is managing threads) and the threads themselves run on the same CPU, so when the OS is running, the thread isn’t and vice versa. We need to make sure we can transition properly between those. So once the OS loads the states and jumps to the PC, this essentially means the OS gives up the control of the CPU to a user level program. In old days, one user-level application crashes may cause the whole OS freeze. Fortunately, In modern operating system, we have memory protections, and we also have preemption possibilities through interrupts.

- How does the dispatcher get control back?

- Internal events: thread returns control voluntarily

- External events: thread gets preempted

Internal Events

Internal events are times when every thread is cooperating and voluntarily gives up its CPU.

A good example is blocking I/O. When we make a system call, and we ask the operating system to do a read(), we give up the CPU (implicitly yielding), so the OS can work on your task by reading data from disk.

- Blocking on I/O

- The act of requesting I/O implicitly yields the CPU

- Waiting on a “signal” from other thread

- Thread asks to wait for thus yards the CPU

- Thread executes a yield()

- Thread volunteers to give up CPU

computePI() {

while(TRUE) {

ComputeNextDigit();

yield(); //sleep is type of yield

}

}

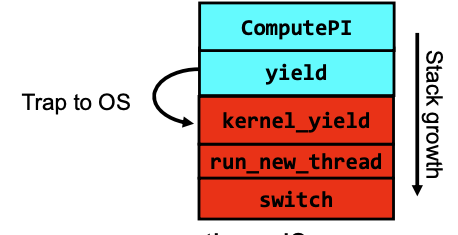

Stack For Yielding Thread

In the diagram above, when we call yield, we transition from user space to the kernel space. We also enter a kernel-level stack (the red ones). For every user-level thread(stack), there is a corresponding kernel-level stack, which remembers the address of yield, so when the kernel-level stack exists, it knows where to find the yield.

- How do we

run_new_thread?

run_new_thread() {

nextThread = PickNextThread();

switch(curThread, nextThread);

ThreadHouseKeeping(); /* Do any cleanup */

}

- How does dispatcher switch to a new thread?

- Save anything next thread may trash: PC, regs, stack pointer (the blue areas)

- Maintain isolation for each thread

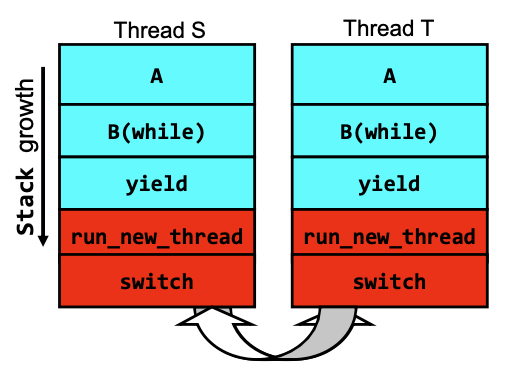

Consider the following code blocks:

proc A() {

B();

}

proc B() {

while(TRUE) {

yield();

}

}

Suppose we have 2 threads: Threads S and T, and they are both running the same code above:

In this particular example, where there’s only two threads in the system, and they both running the same code. What’s going to happen is:

- We are going down the stack for thread

S - When hitting

yield, we switch toT - We then go down the stack for

Tand come back forS

Saving/Restoring state (often called Context Switch)

The switch routine is quite simple. We just save all the registers states of the current thread to a TCB, and load the register states from TCB for the next thread.

Switch(tCur,tNew) {

/* Unload old thread */

TCB[tCur].regs.r7 = CPU.r7;

…

TCB[tCur].regs.r0 = CPU.r0;

TCB[tCur].regs.sp = CPU.sp; // sve the stack pointer

TCB[tCur].regs.retpc = CPU.retpc; /*return addr*/

/* Load and execute new thread */

CPU.r7 = TCB[tNew].regs.r7;

…

CPU.r0 = TCB[tNew].regs.r0;

CPU.sp = TCB[tNew].regs.sp; // load the stack pointer

CPU.retpc = TCB[tNew].regs.retpc;

return; /* Return to CPU.retpc */

}

Now with this in mind, let breakdown the above diagram and figure out the context switch in detail:

- Let’s say the CPU is running thread

S. In theswitchfunction, we update the CPU registers with the threadT’s state, meaning before we hit `return` in the current `switch` function(Thread `S`), we are already in thread `T`'s stack. - Now in thread

T’s stack, the CPU reads the stack pointer, which points to `return` at the bottom of theswitchfunction. Since we are already in threadT’s stack. So thereturnwill exit theswitchfunction, and we will pop up the stack forswitchandrun_new_thread. - Now we are transitioning back to the user-level stack(still in thread

T’s stack). We pop upyieldand hitB(while)again. - Next, thread

Thitsyieldagain due to the while loop, we then enter the kernel space and callrun_new_threadand thenswitch. We are back to step #1

More on switch

- TCB + stacks(user/kernel) contains complete restartable state of a thread. We can put it on any queue for later revival!

- Switching threads is much cheaper than switching processes

- No need to change address space

- Some numbers from Linux:

- Frequency of context switch:

10-100ms - Switching between processes:

3-4 micro sec. - Switching between threads:

100 ns

- Frequency of context switch:

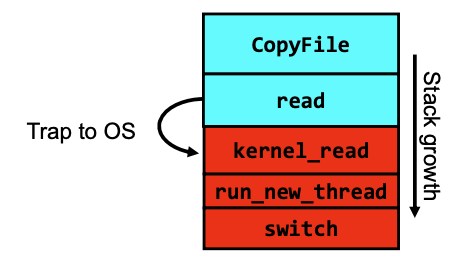

What happens when thread blocks on I/O

- What happens when a thread requests a block of data from the file system?

- User code invokes a system call

- Read operation is initiated

- Run new thread/switch

- Thread communication similar

- Wait for Signal/Join

- Networking

External Events

What happens if thread never does any I/O, never waits and never yield control? We must find a way to let the dispatcher regain the control. We can utilize external events

- Interrupts: signals from hardware or software that stop the running code and jump to kernel

- Timer: like an alarm clock that goes off every some milliseconds

If we make sure that external events occur frequently enough, the dispatcher can regain the control of CPU.

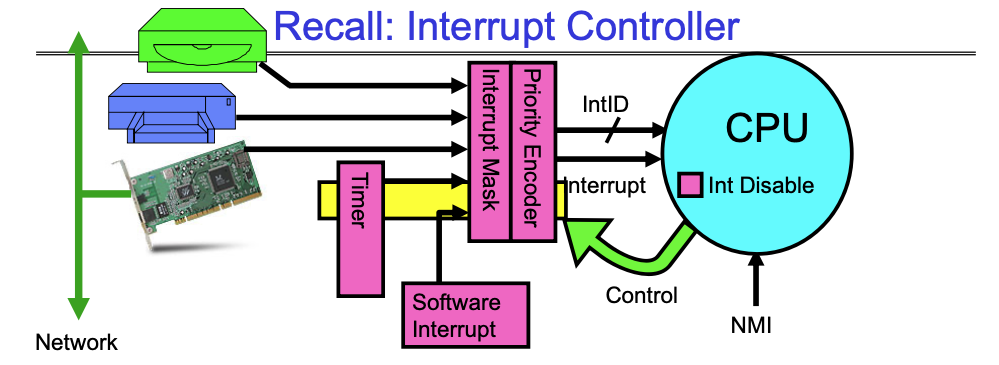

A typical operating system has a bunch of hardwares that are all connected to via interrupt lines to the interrupt controller, and the interrupt controller goes through an interrupt mask (which lets us disable interrupt), and then goes through an interrupt decoder and tells CPU to stop what’s doing to handle an interrupt.

- Interrupts invoked with interrupt lines from devices

- Interrupt controller chooses interrupt request to honor

- Interrupt identity specified with ID line

- Mask enables/disables interrupts

- Priority encoder picks highest enabled interrupt

- Software Interrupt Set/Cleared by Software

- CPU can disable all interrupts with internal flag

- Non-Maskable Interrupt line (NMI) can’t be disabled

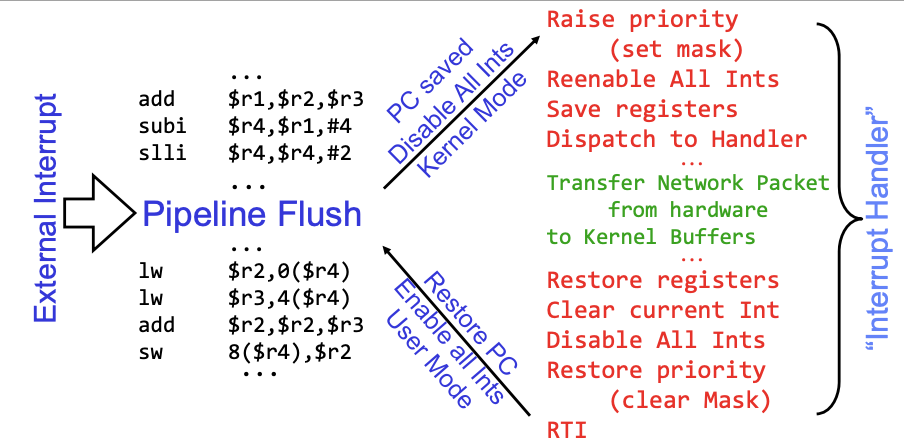

Example: Network Interrupt

The CPU is running some code here and a network interrupt kicks in. The pipeline gets flushed first, and the current PC gets saved. Then we enter the kernel mode (red code). In kernel, we save the interrupt states, then call the network handler to process the networking data (green code). After we finish processing logic, we go back to the kernel mode and restore the previously saved interrupt states. Next, we continue to execute the code that got previously interrupted (the second part of the assembly code).

Note that An interrupt is a hardware-invoked context switch. There is no separate step to choose what to run next. The kernel always run the interrupt handler immediately.

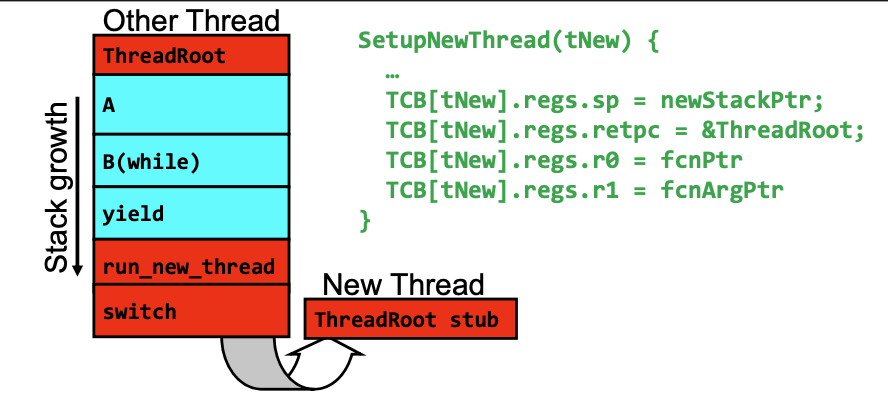

How do we make a new thread?

- Initialize Register fields of TCB

- Stack pointer made to point at stack

- PC return address -> OS (asm) routine

ThreadRoot() - Two arg registers (

a0anda1) initialized tofcnPtrandfcnArgPtrrespectively

- Initialize stack data?

- Minimal initialization -> setup return to go to beginning of

ThreadRoot()- Important part of stack frame is in registers for RISC-V (ra)

- X86: need to push a return address on stack

- Think of stack frame as just before body of

ThreadRoot()really gets started

- Minimal initialization -> setup return to go to beginning of

- How do we make a new thread?

- Setup TCB/kernel thread to point at new user stack and ThreadRoot code

- Put pointers to start function and args in registers or top of stack

- This depends heavily on the calling convention (i.e. RISC-V vs x86)

- Eventually, run_new_thread() will select this TCB and return into beginning of

ThreadRoot()- This really starts the new thread

ThreadRoot()is the root for the thread routine:

ThreadRoot(fcnPTR,fcnArgPtr) {

DoStartupHousekeeping();

UserModeSwitch(); /* enter user mode */

Call fcnPtr(fcnArgPtr);

ThreadFinish();

}

- Startup Housekeeping

- Includes things like recording start time of thread

- Other statistics

- Final return from thread returns into

ThreadRoot()which callsThreadFinish()ThreadFinish()wake up sleeping threads

Synchronization

Correctness with Concurrent Threads

- Non-determinism:

- Scheduler can run threads in any order

- Scheduler can switch threads at any time

- This can make testing very difficult

- Independent Threads

- No state shared with other threads

- Deterministic, reproducible conditions

- Cooperating Threads

- Shared state between multiple threads

Atomic Operations

- To understand a concurrent program, we need to know what the underlying indivisible operations are!

- Atomic Operation: an operation that always runs to completion or not at all

- It is indivisible: it cannot be stopped in the middle and state cannot be modified by someone else in the middle

- Fundamental building block, if no atomic operations, then have no way for threads to work together

- On most machines, memory references and assignments (i.e. loads and stores) of words are atomic

- Many instructions are not atomic

- Double-precision floating point store often not atomic

- VAX and IBM 360 had an instruction to copy a whole array

Locks

- Lock: prevents someone from doing something

- Lock before entering critical section and before accessing shared data

- Unlock when leaving, after accessing shared data

- Wait if locked

- Important idea: all synchronization involves waiting

- Locks need to be allocated and initialized:

structure Lock mylockorpthread_mutex_t mylock;lock_init(&mylock)ormylock = PTHREAD_MUTEX_INITIALIZER;

- Locks provide two atomic operations:

acquire(&mylock)wait until lock is free; then mark it as busy- After this returns, we say the calling thread holds the lock

release(&mylock)– mark lock as free- Should only be called by a thread that currently holds the lock

- After this returns, the calling thread no longer holds the lock

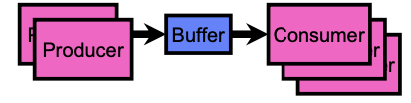

Producer-Consumer with a Bounded Buffer

- Problem Definition

- Producer(s) put things into a shared buffer

- Consumer(s) take them out

- Need synchronization to coordinate producer/consumer

- Don’t want producer and consumer to have to work in lockstep, so put a fixed-size buffer between them

- Need to synchronize access to this buffer

- Producer needs to wait if buffer is full

- Consumer needs to wait if buffer is empty

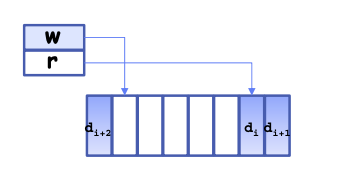

- Circular Buffer

typedef struct buf {

int write_index;

int read_index;

void *entries[BUFSIZE];

} buf_t;

- How to tell if the queue is empty

- If the read pointer hits the write pointer

- How to tell if the queue is full

- If the write pointer hits the read pointer

// synchronization using locks

mutex buf_lock = <initially unlocked>

Producer(item) {

acquire(&buf_lock);

while (buffer full) {

release(&buf_lock); // give consumer a chance to aquire the lock

acquire(&buf_lock);

}

enqueue(item);

release(&buf_lock);

}

Consumer() {

acquire(&buf_lock);

while (buffer empty) {

release(&buf_lock); // give producer a chance to aquire the lock

acquire(&buf_lock);

}

item = dequeue();

release(&buf_lock);

return item

}

This works, but waste a LOT of CPU cycles by frequently releasing and acquiring the lock! So locks is not the best choice for this consumer producer problem.

Higher-level Primitives than Locks

- What is right abstraction for synchronizing threads that share memory?

- Want as high a level primitive as possible

- Good primitives and practices important!

- Since execution is not entirely sequential, really hard to find bugs, since they rarely happen

- UNIX is pretty stable now, but up until about mid-80s (10 years after started), systems running UNIX would crash every week or so - concurrency bugs

- Synchronization is a way of coordinating multiple concurrent activities that are using shared state