Multicore Programing

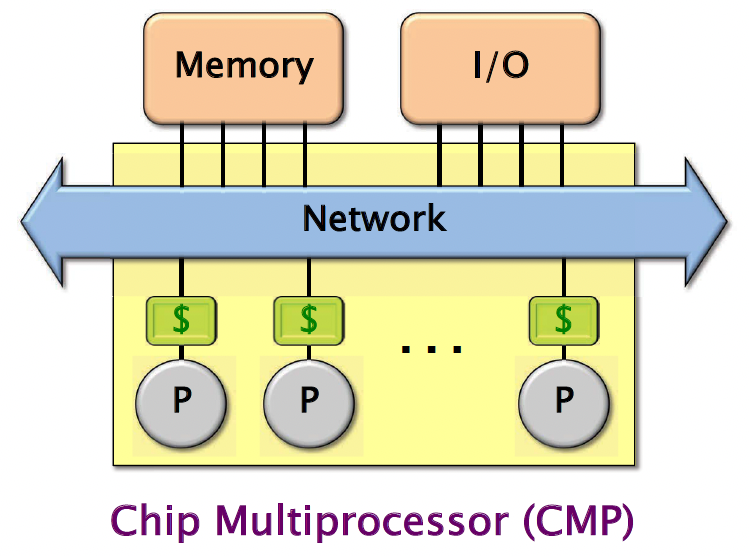

Abstract Multicore Architecture

Here we have a whole bunch of processors. They each have a cache, so that’s indicated with the dollar sign. And usually they have a private cache as well as a shared cache, so a shared last level cache, like the L3 cache. And then they’re all connected to the network. And then, through the network, they can connect to the main memory. They can all access the same shared memory. And then usually there’s a separate network for the I/O as well, even though I’ve drawn them as a single network here, so they can access the I/O interface. And potentially, the network will also connect to other multiprocessors on the same system. And this abstract multicore architecture is known as a chip multiprocessor, or CMP.

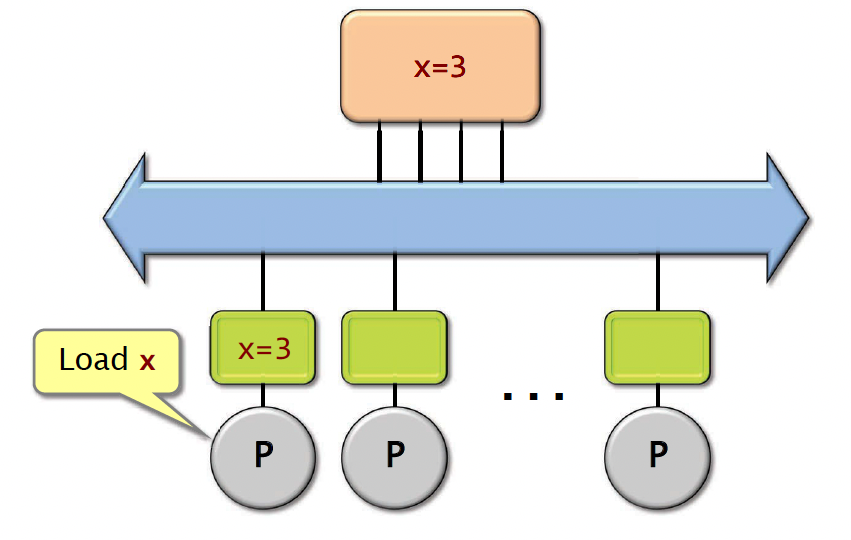

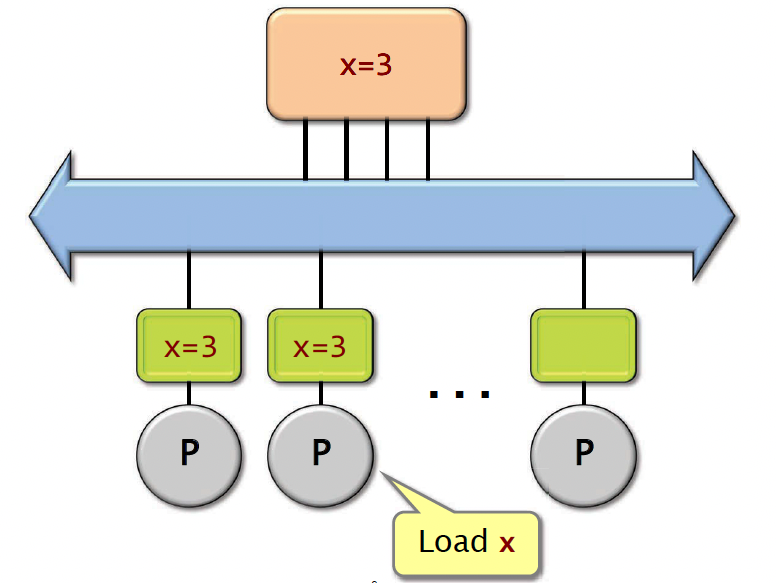

Shared-Memory Hardware

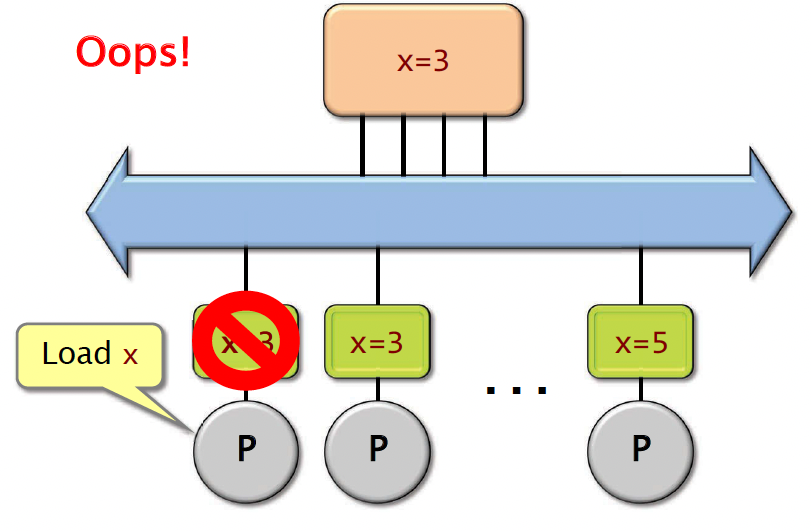

Let’s say we have a value x=3 in memory. If one processor says, we want to load x, what happens is that processor reads this value from a main memory, brings it into its own cache, and then it also reads the value, loads it into one of its registers. And it keeps this value in cache.

Now, what happens if another processor wants to load x? It just does the same thing. It reads the value from main memory, brings it into its cache, and then also loads it into one of the registers. And then same thing with another processor.

It turns out that you don’t actually always have to go out to main memory to get the value. If the value resides in one of the other processor’s caches, you can also get the value through the other processor’s cache.

Let’s say there is a processor wants to set x equals to 5, and it stores that result in its own cache. Now what happens when the first processor wants to load x? Well, it seems that the value of x is in its own cache, so it’s just going to read the value of x there, and it gets a value of 3. The problem is the cache here is stale, so the value there is invalid.

one of the main challenges of multicore hardware is to try to solve this problem of cache coherence - making sure that the values in different processors’ caches are consistent across updates.

MSI Protocol

One basic protocol for solving this problem is known as the MSI protocol. Each cache line is labeled with a state:

M: cache block has been modified. No other caches contain this block inMorSstates.S: other caches may be sharing this block.I: cache block is invalid (same as not there).

Most of the machines have 64byte cache lines.

To solve the problem of cache coherency, when one cache modifies a location, it has to inform all the other caches that their values are now stale. So it’s going to invalidate all of the other copies of that cache line in other caches by changing their state from S to I.

So let’s say that the second processor wants to store y equals 5. Let’s see how it works

Concurrency Platforms

- Programming directly on processor cores is painful and error-prone.

- A concurrency platform abstracts processor cores, handles synchronization and communication protocols, and performs load balancing.

- Examples

- Pthreads and WinAPI threads

- Threading Building Blocks (TBB)

- OpenMP

- Cilk

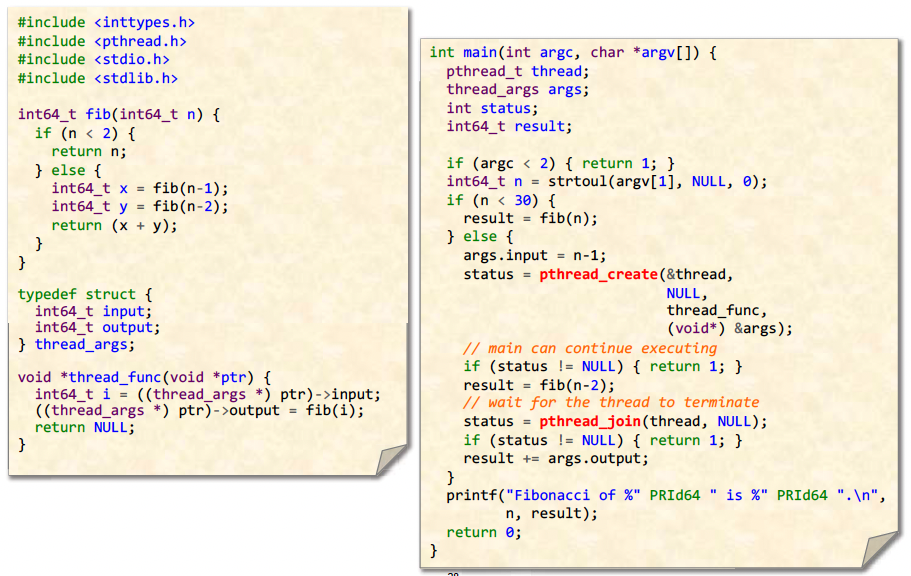

Fibnacci Program

We use the Fibnacci problem as an example. This recursive program is a poor way to compute the nth Fibonacci number, but it provides for a good didactic example.

int64_t fib(int64_t n) {

if(n<2) {

return n;

} else {

int64_t x = fib(n-1);

int64_t y = fib(n-2);

return (x+y);

}

}

Key idea for parallelization

The calculations of fib(n-1) and fib(n-2) can be executed simultaneously without mutual interference.

pthreads

- Standard API for threading specified byANSI/IEEE POSIX 1003.1-2008.

- Do-it-yourself concurrency platform.

- Built as a library of functions with “special” non-C semantics.

- Each thread implements an abstraction of a processor, which are multiplexed onto machineresources.

- The number of threads that you create doesn’t necessarily have to match the number of processors you have on your machine.

- Threads communicate though shared memory.

- Library functions mask the protocols involvedin interthread coordination.

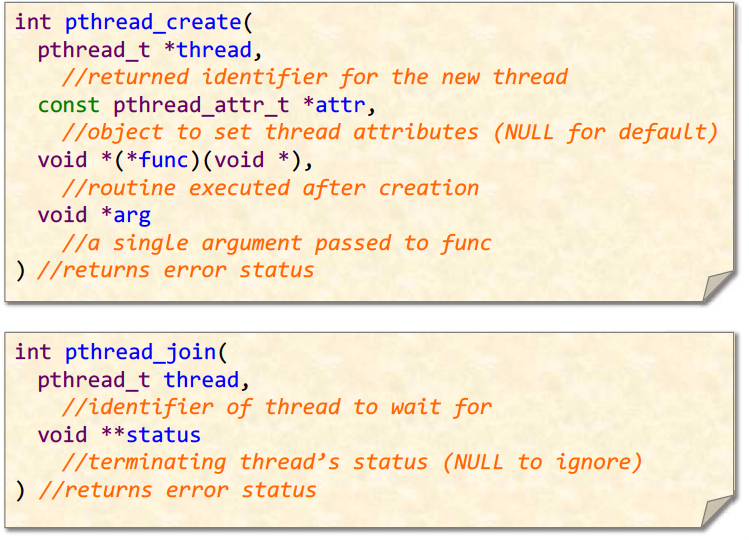

Key pthread functions

Here is the code for running fib concurrently using pthreads

Note that the code doesn’t recursively create threads. It only creates one thread at the top level. The fib(n-2) executes on the same thread as the main().

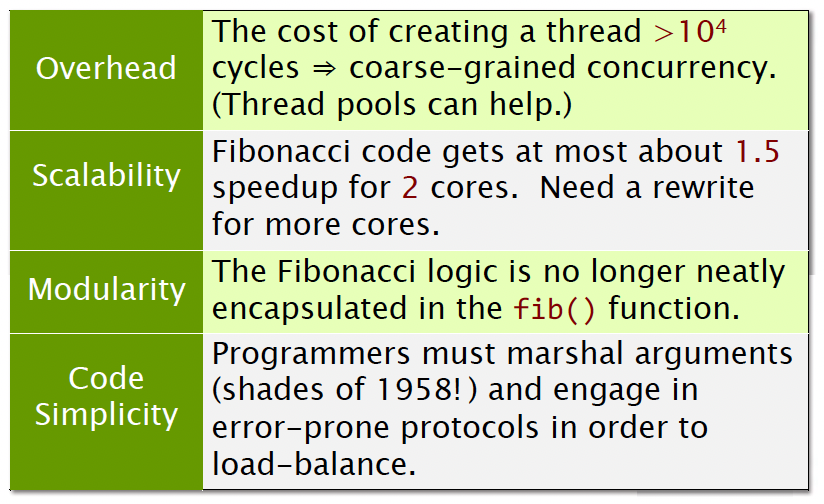

Issues with pthreads

The 1.5x speed up is due to one thread computing fib(n-2) and the other is computing fib(n-1). So they’re not exactly equal.

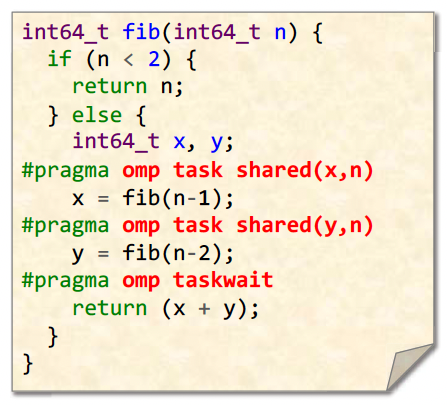

OpenMP

- Specification by an industry consortium.

- Several compilers available, both open-source and proprietary, including GCC, ICC,Clang, and Visual Studio.

- Linguistic extensions to C/C++ and Fortran inthe form of compiler pragmas.

- Runs on top of native threads.

- Supports loop parallelism, task parallelism,and pipeline parallelism.

OpenMP provides many pragma directivesto express common patterns, such as

- parallel for for loop parallelism,

- reduction for data aggregation,

- directives for scheduling and data sharing.

OpenMP supplies a variety ofsynchronization constructs, such asbarriers, atomic updates, and mutual-exclusion (mutex) locks.