Parallel Storage Allocation

Heap Storage in C

- Allocation

void* malloc(size_t s); - allocate and return a pointer to a block of memory containing at least s bytes.

- Aligned allocation

void* memalign(size_t a, size_t s); - allocate and return a pointer to a block of memory containing at least s bytes, aligned to a multiple of a where a must be an exact power of 2: 0 == ((size_t)memalign(a, s)) % a. One reason to use memalign is to align the memory allocation to cache line to reduce the number of times of cache misses. Another reason is that the vectorization operations also requires the memory addresses to aligned with power of 2.

- Deallocation

void free(void *p); - p is a pointer to a block of memory returned by malloc() or memalign(). Deallocate the block.

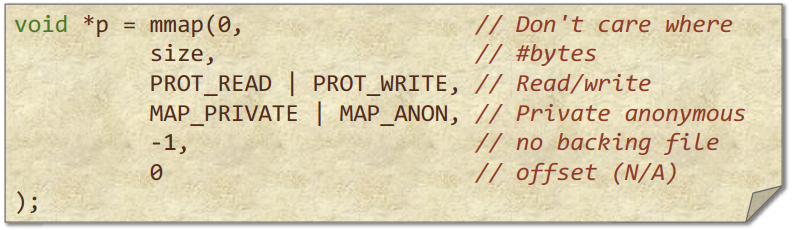

Allocating Virtual Memory

The mmap() system call can be used to allocate virtual memory by memory mapping. It usually used to treat some files on the disk as part of memory, so that when you write to that memory region it also backs it up on the disk. In this case, we’re using mmap to allocate virtual memory without having any backing file.

- The first param means where I want to allocate the memory.

0means don’t care. - The second params indicates how much memory I want to allocate in bytes.

- The thrid params is the permissions.

MAP_PRIVATEmeans the memory is private to the process that’s allocating it.MAP_ANONmeans there is no name associated with the memory region

The Linux kernel finds a contiguous, unused region in the address space of the application large enough to hold size bytes, modifies the page table, and creates the necessary virtual-memory management structures within the OS to make the user’s accesses to this area “legal” so that accesses won’t result in a segfault.

Properties of mmap()

mmap()is lazy. It does not immediately allocate physical memory for the requested allocation.- Instead, it populates the page table with entries pointing to a special zero page and marks the page as read only.

- The first write into such a page causes a page fault.

- At that point, the OS allocates a physical page, modifies the page table, and restarts the instruction.

- You can

mmap()a terabyte of virtual memory on a machine with only a gigabyte of DRAM. - A process may die from running out of physical memory well after after the mmap() call.

What’s the difference between malloc() and mmap()

- The functions

malloc()andfree()are part of the memory-allocation interface of the heap-management code in the C library. - The heap-management code uses available system facilities, including

mmap(), to obtain memory (virtual address space) from the kernel. - The heap-management code within

malloc()attempts to satisfy user requests for heap storage by reusing freed memory whenever possible. - When necessary, the

malloc()implementation invokes mmap() and other system calls to expand the size of the user’s heap storage.

Q: Why just use `mmap` instead?

One anwser is that you might have free storage from before that you would want to reuse. It turns out that mmap is relatively heavy weight. It works on a page granularity. So if you wnat to do a small allocation, it’s quite wasteful to allocate an entire page for that allocation and not reuse it. You’ll get very bad external fragmentation. It also goes through all of the overhead of security of the OS and updaing the page table and so on. Whereas, use malloc is pretty fast for most allocations, and especially if you have temporal locality where you allocate something that you just recently freed. So your program will be pretty slow if you use mmap all the time even for small allocations.

Address Translation

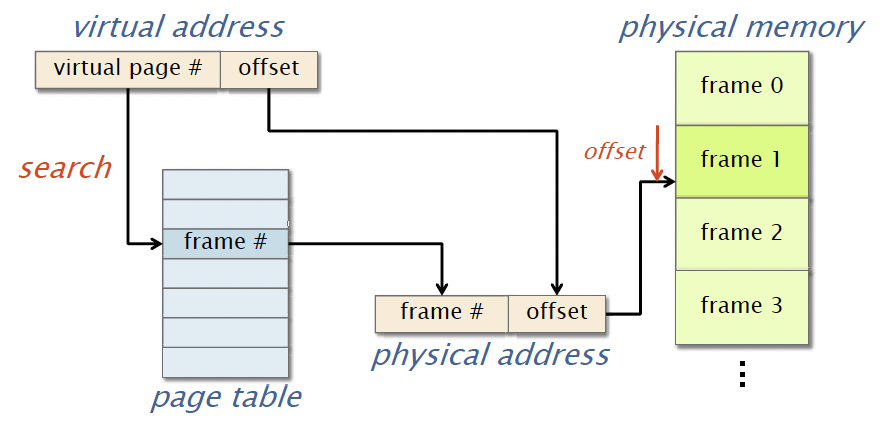

When you access memory location, you access via the virtual address, which can be divieded into two parts, where the lower order bits store the offset and higher order bits store the virtual page numeber.

If the virtual page does not reside in physical memory, a page fault occurs. When that happens,the OS will see that the process acutally has permissions to look at the memory region, and it will set the permissions and place the entry into the page table so that you can get the appropriate physical address. Otherwise, you’ll get a segmentation fault.

Since page-table lookups are costly, the hardware contains a translation lookaside buffer (TLB) to cache recent page-table lookups. The page-table store pages which are typically 4kb. Nowadays, there are also huge pages, which can be a couple of megabytes. And most of the accesses in your program are going to be near each other. So they’re likely going to reside on the same page for accesses that have been done close together in time. Therefore, you’ll expect that many of your recent accesses are going to be stored in the TLB if your program has locality, either spatial or temporal locality or both.

So how this architecture works is that

- The processors check whether the virtual address you’re looking for is in TLB. If it’s not, it’s going to go to the page table and look it up. And then if it finds that there, then it’s going to store that entry into the TLB.

- Next, it’s going to get this physical address that it found from the TLB and look it up into the CPU cache. If it finds it there, it gets it. If it doesn’t, then it goes to DRAM to satisfy the request.

Most of modern machines acutally have an optimization that allow you to do TLB accesses in parallel with the L1 cache access. So the L1 cache acutally uses virtual addresses instead of Physical addresses, and this reduces the latency of a memory access.

Traditional Linear Stack

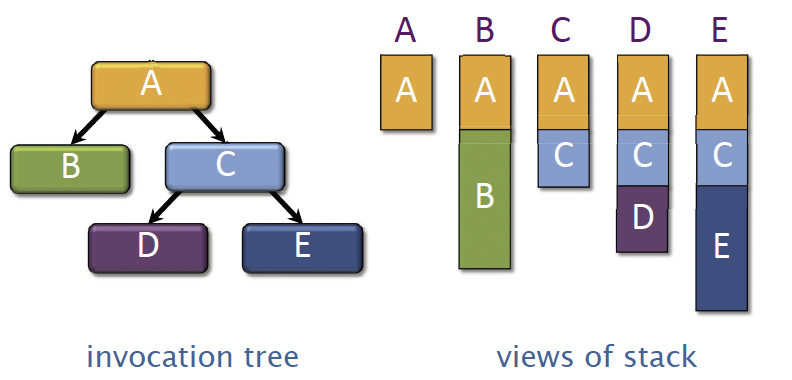

So when you execute a serial c and c++ program, you’re using a stack to keep track of the function calls and local variables that you have to save. An execution of a serial C/C++ program can be viewed as a serial walk of an invocation tree.

In the example below, we have function A calls function B and C, function C calls D and E

Rule for pointers: A parent can pass pointers to its stack variables down to its children, but not the other way around.

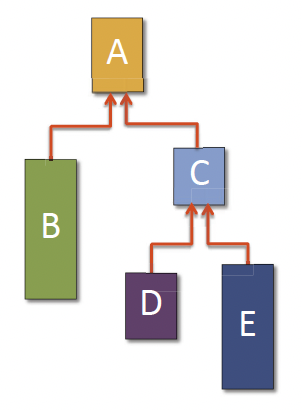

Cactus Stack

A cactus stack supports multiple views in parallel. In the serial stack, the later allocated memory overrides the previous memory in stack. In parallel situtaions, function B, D and E could execute in parallel, and they still want to share the same stack view of A. So how to do that?

One solution is to allocate the stack frames on heap. And each of the stack frame has a pointer to its parant stack frame.

So whenever you do a function call, you’re going to do a memory allocation from the heap to get a new stack frame. And then when you finish a function, you’re going to pop something off of this stack, and free it back to the heap.

Basic Properties of Staroage Allocators

Allocator Speed is the number of allocations and deallocations per second that the allocator can sustain.

Q. Is it more important to maximize allocator speed for large blocks or small blocks? A. Small blocks!

Q. Why? A. Typically, a user program writes all the bytes of an allocated block. A large block takes so much time to write that the allocator time has little effect on the overall runtime. In contrast, if a program allocates many small blocks, the allocator time can represent a significant overhead.

Fragmentation

-

The user footprint is the maximum over time of the number

Uof bytes in use by the user program (allocated but not freed). This is measuring the peak memory usage. It’s not necessarily equal to the sum of the sizes that you have allocated so far, because you might have reused some of that. So the user footprint is the peak memory usage and number of bytes. -

The allocator footprint is the maximum over time of the number

Aof bytes of memory provided to the allocator by the operating system. The reason why the allocator footprint could be larger than the user footprint, is that when you ask the OS for some memory, it could give you more than what you asked for. -

The fragmentation is

F = A/U.

Modern 64-bit processors provide about $2^{48}$ bytes of virtual address space. A big server might have $2^{40}$ bytes of physical memory.

- Space overhead: Space used by the allocator for bookkeeping.

- Internal fragmentation: Waste due to allocating larger blocks than the user requests.

- External fragmentation: Waste due to the inability to use storage because it is not contiguous.

- Blowup: For a parallel allocator, the additional space beyond what a serial allocator would require.

PARALLEL ALLOCATION STRATEGIES

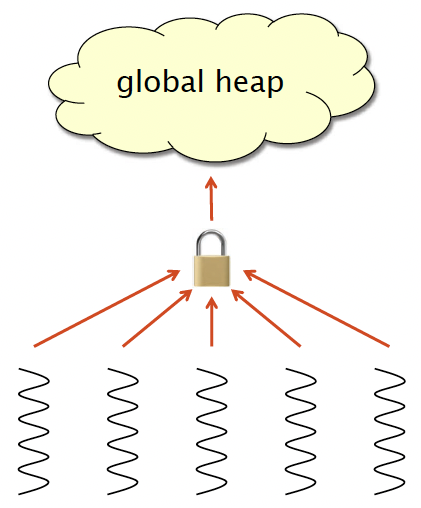

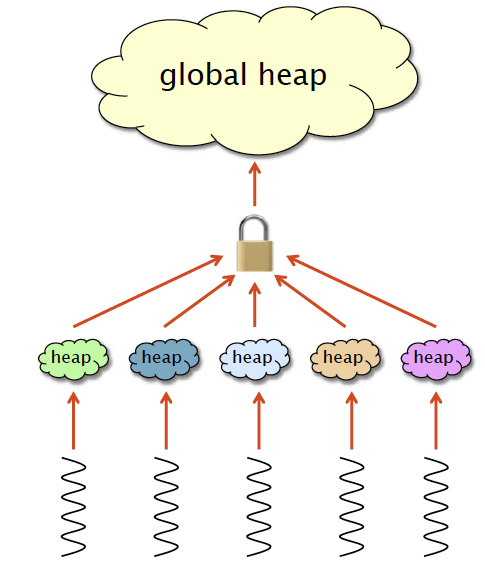

Strategy1:GlobalHeap

- Default C allocator.

- All threads (processors) share a single heap.

- Accesses are mediated by a mutex (or lock-free synchronization) to preserve atomicity.

- Pros

- Blowup = 1

- Cons

- Slow — acquiring a lock is like an L2-cache access.

- Contention can inhibit scalability.

Ideally, as the number of threads (processors) grows, the time to perform an allocation or deallocation should not increase. The most common reason for loss of scalability is lock contention.

Q. Is lock contention more of a problem for large blocks or for small blocks? A. Small blocks!

Q. Why? A. Typically, a user program writes all the bytes of an allocated block, making it hard for a thread allocating large blocks to issue allocation requests at a high rate. In contrast, if a program allocates many small blocks in parallel, contention can be a significant issue.

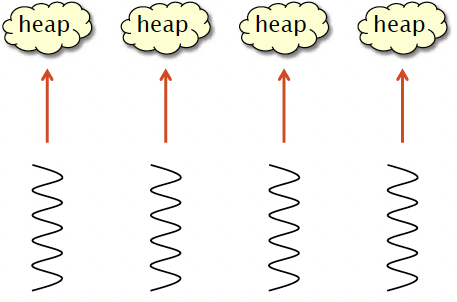

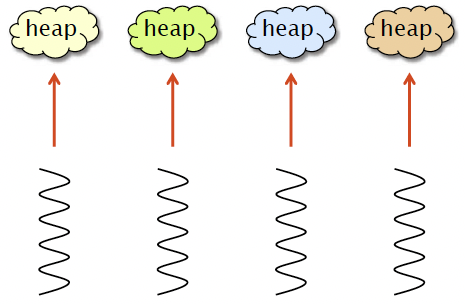

Strategy2:LocalHeaps

- Each thread allocates out of its own heap.

- No locking is necessary

- Pros

- Fast — no synchronization.

- Cons

- Suffers from memory drift: blocks allocated by one thread are freed on another -> unbounded blowup.

Strategy3:LocalOwnership

- Each object is labeled with its owner.

- Freed objects are returned to the owner’s heap.

- Pros

- Fast allocation and freeing of local objects.

- Resilience to false sharing.

- Cons

- Freeing remote objects requires synchronization. Blowup ≤ P.

The Hoard Allocator

- P local heaps.

- 1 global heap.

- Memory is organized into large superblocks of size S.

- Only superblocks are moved between the local heaps and the global heap.

- Pros

- Fast.

- Scalable.

- Bounded blowup.

- Resilience to false sharing.

Hoard Allocation

Assume without loss of generality that all blocks are the same size (fixed-size allocation). x = malloc() on thread i

if (there exists a free object in heap i) {

x = an object from the fullest nonfull superblock in i’s heap;

} else {

if (the global heap is empty) {

B = a new superblock from the OS;

} else {

B = a superblock in the global heap;

}

set the owner of B to i;

x = a free object in B;

}

return x;

Hoard Deallocation

Let u[i] be the in-use storage in heap i, and let a[i] be the storage owned by heap i. Hoard maintains the following invariant for

all heaps i:

u[i] ≥ min(a[i] - 2S, a[i]/2),

where S is the superblock size.

free(x), where x is owned by thread i:

put x back in heap i;

if (u[i] < min(a[i] - 2S, a[i]/2)) {

move a superblock that is at least 1/2 empty from

heap i to the global heap;

};

Other Solutions

jemalloc is like Hoard, with a few differences:

jemallochas a separate global lock for each different allocation size.jemallocallocates the object with the smallest address among all objects of the requested size.jemallocreleases empty pages usingmadvise(p, MADV_DONTNEED, ...), which zeros the page while keeping the virtual address valid.- jemalloc is a popular choice for parallel systems due to its performance and robustness. SuperMalloc is an up-and-coming contender. (See paper by Bradley C. Kuszmaul.)

SuperMalloc is an up-and-coming contender. (See paper by Bradley C. Kuszmaul.)

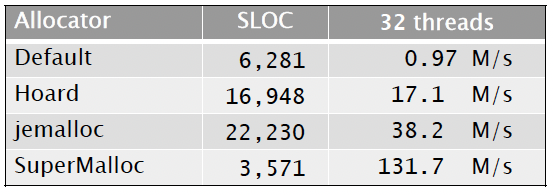

Allocator Speeds