How Stable Diffusion Work

Introduction

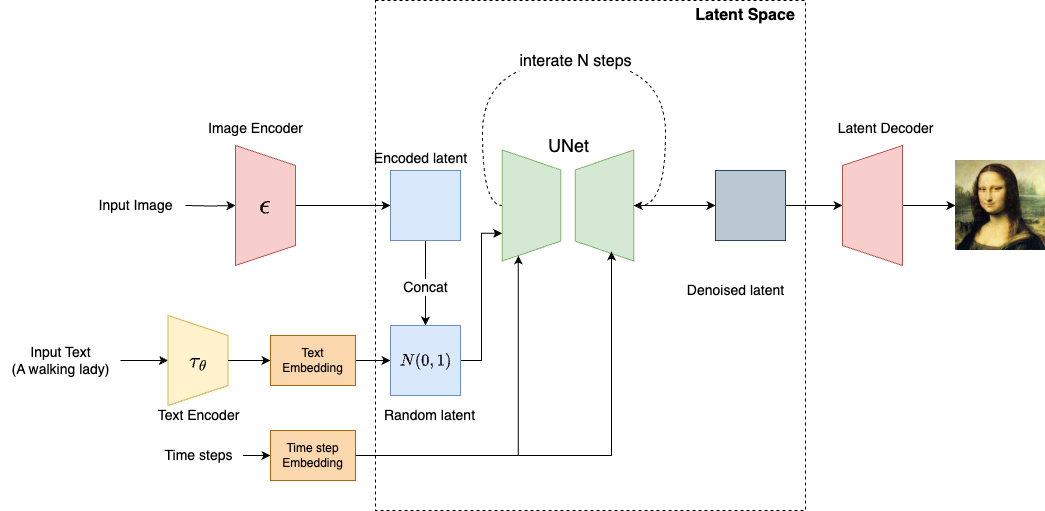

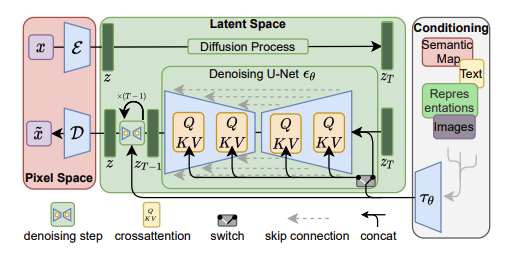

In the previous post, we explored the theory behind diffusion models. While the original diffusion model serves as more of a proof of concept, it highlights the immense potential of multi-step diffusion models compared to one-pass neural networks. However, it comes with a significant drawback: the pre-trained model operates in pixel space, which is computationally intensive. In 2022, researchers introduced Latent Diffusion Models, which effectively addressed the performance limitations of earlier diffusion models. This approach later became widely known as Stable Diffusion.

At its core, Stable Diffusion contains a collection of models that work together to produce the output image

- Tokenizer: Converts a text prompt into a sequence of tokens.

- Text Encoder: A specialized Transformer-based language model(CLIP), converting tokens into text embeddings.

- Variational Autoencoder (VAE): Encodes images into a latent space and reconstructs them back into images.

- U-Net: The core of the denoising process. This architecture models the noise removal steps by taking inputs such as noise, time-step data, and a conditional signal (e.g., a text representation). It then predicts noise residuals, which guide the image reconstruction process.

The power of stable diffusion models comes from the ability to generate images through text. So how does the text prompt affects the image generation process? This turns out to be a complex process involving the coordination of several models. Let’s walk through it step by step.

CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training)

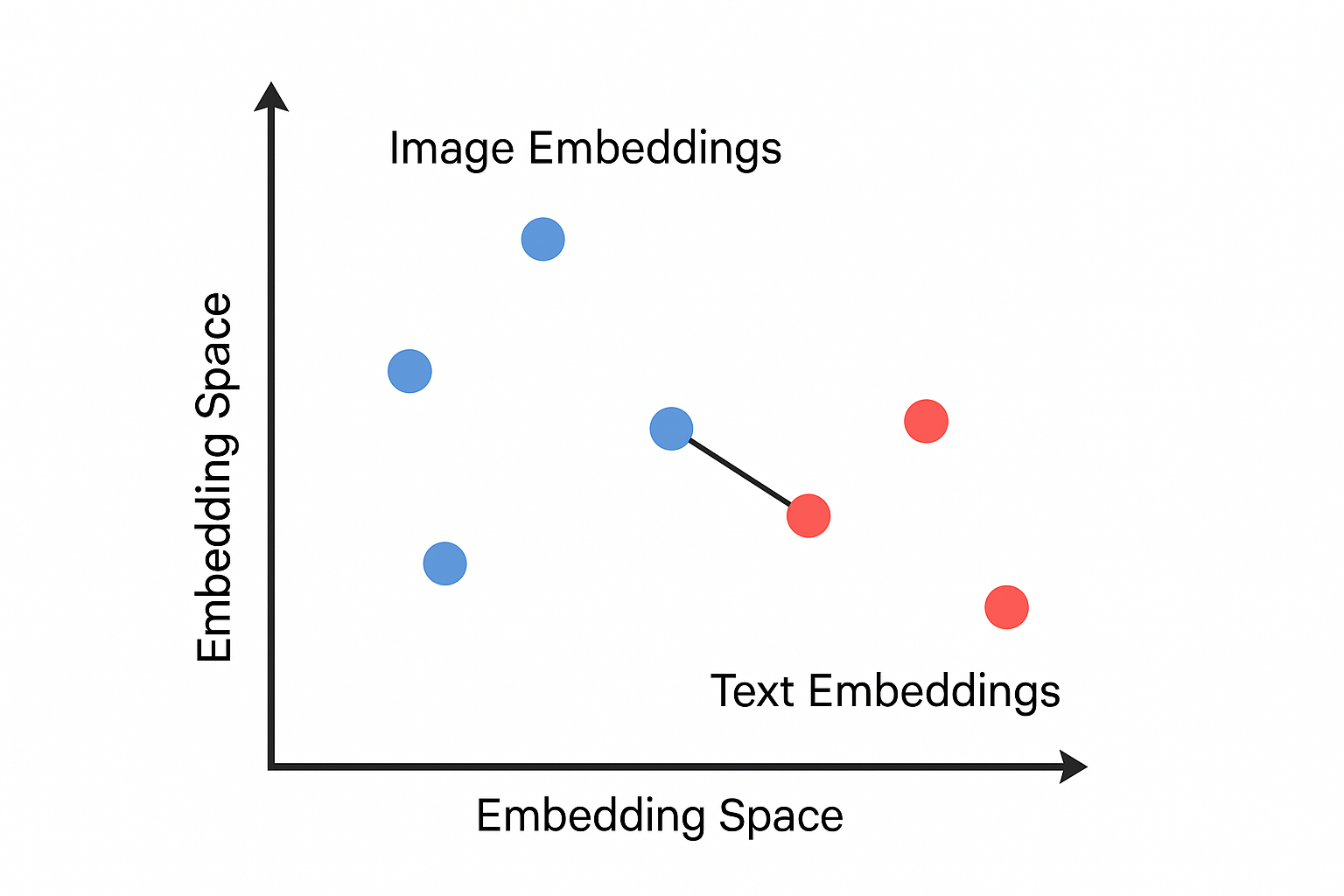

Contrastive learning is a family of self-supervised learning methods that help models learn meaningful representations from data that don’t have labels. The key idea is images that show similar objects should have similar representations

CLIP is one of the Contrastive models. It was first introduced by openAI. The goal is to learn a shared embedding space where text descriptions and images are mapped to vectors that are semantically aligned.

The CLIP model is trained using 400 million (image, text) pairs, where the text is the caption of the image. Thus, after training, the model can encode images and text into a vector that can best represent the images’ content in the CLIP embedding space.

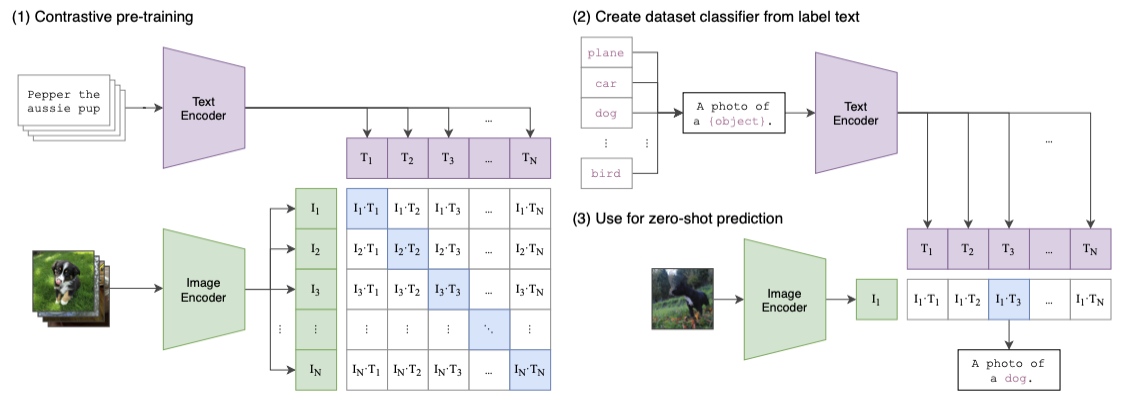

Here is the high-level steps of the training process:

- Let a batch of images goes through an image encoder(a ResNet50/ViT model) to produce the feature embeddings $I_e$.

- Let a batch of the corresponding text caption go through a text encoder(a Transformer model) to produce the text embedding $T_e$.

- Calculate the embedding cosine similarities between $I_e$ and $T_e$

- Update both encoders’ weights to maximize the similarity for the correct pairs (the blue squares along the diagonal direction in the diagram)

- Update both encoders’ weights to minimize the similarity for the incorrect pairs (white squares in the diagram)

Once the model is pre-trained, it proceeds through a zero-shot transfer learning phase. Due to length of this post, we won’t cover it in detail here—refer to the original CLIP paper for a thorough explanation.

In Stable Diffusion, only the CLIP text encoder is used to convert text prompts into embeddings. These text embeddings then condition the image generation process. Let’s take a look at one example:

prompt = "a running dog"

# convert prompt to tokens

input_tokens = clip_tokenizer(

prompt,

return_tensors = "pt"

)["input_ids"]

print(input_tokens) # [49406, 320, 2761, 7251, 49407]

clip_text_encoder = CLIPTextModel.from_pretrained(

"runwayml/stable-diffusion-v1-5",

subfolder = "text_encoder",

cache_dir=CACHE_DIR

)

# encode input_tokens to embeddings

text_embeds = clip_text_encoder(input_tokens)[0]

# each input token is encoded into a 768-dim vector

print(text_embeds) # ([1, 5, 768])

For Stable Diffusion 1.5, each token will be encoded as a 768 dimensional vector in the CLIP embedding space. They will be used later in the downstream of the network.

Variational Autoencoder (VAE)

The VAE in Stable Diffusion doesn’t control the image generation process. Instead, it compresses images into a lower-dimensional latent representation before diffusion, and decompresses the final latent back into an image after the diffusion model has finished sampling.

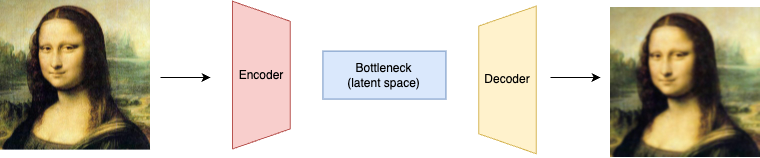

The Autoencoder Architecture

Before we dive into VAEs, it’s important to first understand the architecture of Autoencoder. Autoencoder is a likelihood-based approach for image generation. The Autoencoder architecture consists of three main components: the encoder, the bottleneck(or latent space), and the decoder.

- The encoder compress the input data into a “latent-space” representation, which is a low-dimensional space that captures the essential features of the input data.

- The bottleneck layer is the smallest layer that holds the compressed representation

- The decoder reconstructs the input data from the compressed representation

Training an Autoencoder is a self-supervised process that focuses on minimizing the difference between the original data and its reconstructed version. The goal is to improve the decoder's ability to accurately reconstruct the original data from the compressed latent representation. At the same time, the encoder becomes better at compressing the data in a way of preserving critical information, ensuring that the original data can be effectively reconstructed.

If the model is well-trained, the encoder can be used separately to perform data dimensional reduction. It maps images with similar features (e.g., animals, trees) to nearby regions in latent space. For example, images of dogs will cluster closer to each other than to images of trees in the latent space.

Latent Space

What is latent space, and why is it helpful in Autoencoder or Stable Diffusion?

- Reduced Dimensions: Images in pixel space can be very high-dimensional (e.g., a

512×512RGB image has512 × 512 × 3pixels). Operating in a latent space often reduces the dimensionality by a large factor (e.g., down to64×64or32×32with several channels), which means fewer computations are required. - Faster Sampling: The diffusion process, which involves many iterative steps, becomes much faster when each step is operating on a compressed representation.

- Memory Efficiency: Lower-dimensional representations use significantly less memory. This allows for training and sampling on devices with more limited memory (like GPUs) and enables the model to work with larger batch sizes.

- Preserving Semantics: The latent space is designed to capture the high-level, semantic features of an image (like shapes, object positions, and overall style) rather than every fine-grained pixel detail. This focus on semantics allows the diffusion process to operate on the essential content of the image.

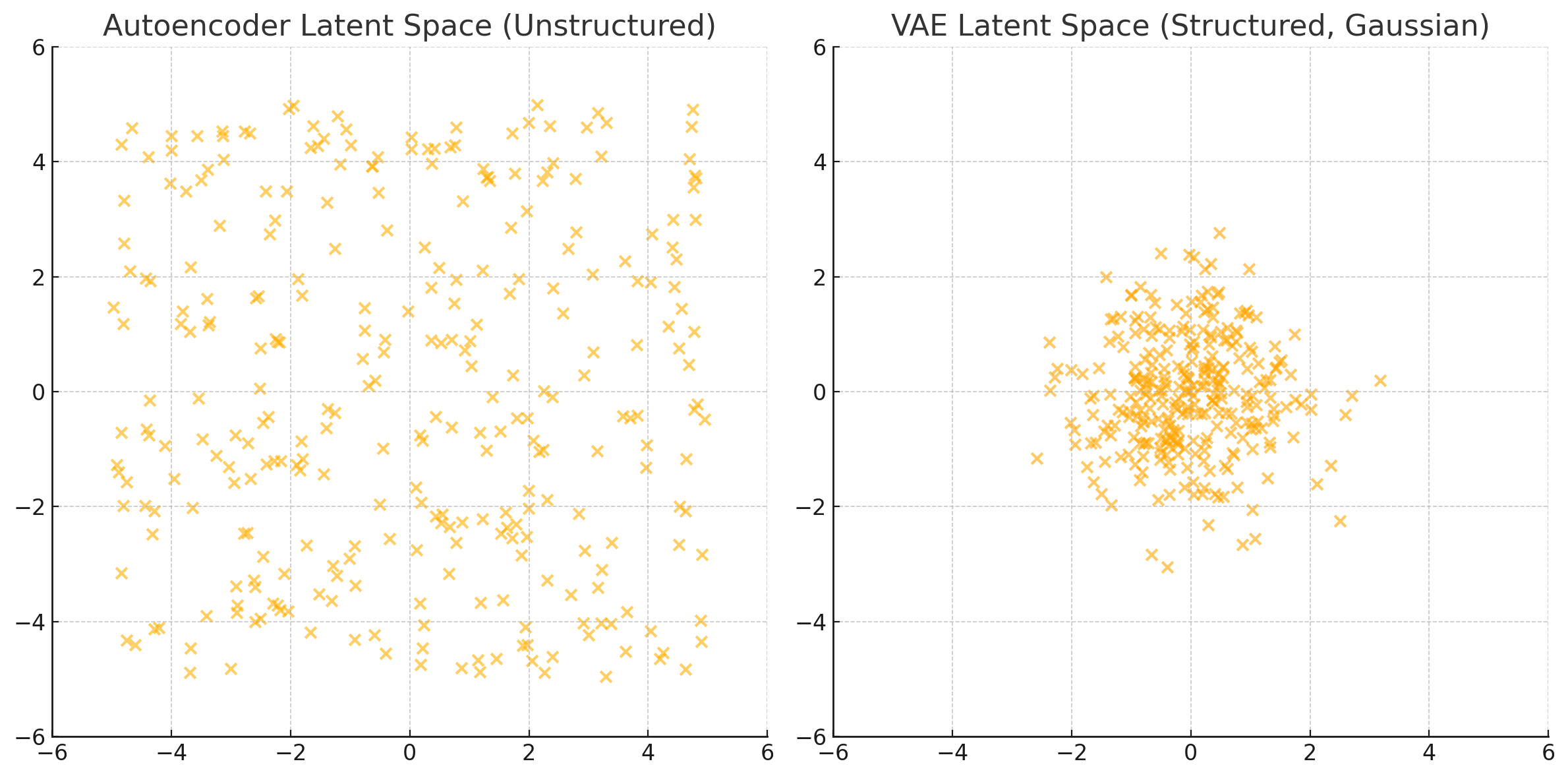

Variational Bayes

With the Autoencoder architecture, a natural idea for generating new images would be to randomly sample points from this latent space and run them through the decoder. Unfortunately, this approach won’t produce meaningful images mainly because the latent space is unstructured and disorganized. For example, if you sample a random latent vector (say, from $N(0,1)$), there’s no guarantee it maps to a valid image.

That is why most of modern implementation of Autoencoders regularize the latent space. VAE is the most famous type of regularized autoencoder. The latent space produced by VAE is structured and continuous, following a standard Gaussian distribution. This makes it easy to sample new points and interpolate smoothly between them

VAE was first introduced in 2013 in this paper named Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. The idea is that, in order to reconstruct an image from a latent vector, we need to calculate the conditional probability $p(x|z)$, where $p(z)$ is a latent distribution that capture the core features of the images. To make this process computable, we assume $p(z)$ follows the standard Gaussian distribution: $p(z) = N(0, 1)$. This allows us to compute the likelyhood $p(x|z)$.

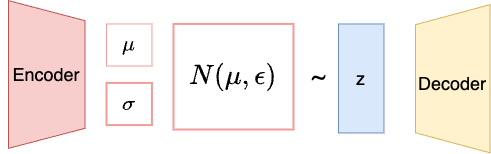

Then the question is how do we produce this Gaussian Distribution? That’s where VAE kicks in, it learns the parameter $\mu$ and $\sigma$, which is an optimization process usually known as variational Bayes. Here is the process:

- We train a deep encoder to estimate these parameters $\mu$ and $\sigma$ from the images

- Then we use a decoder to reconstruct images from a sampled latent variable

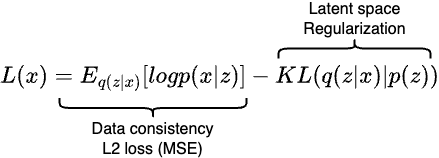

- Compare the reconstructed images with the original images with the following loss function:

The first part of the equation simply measures how well our model can reconstruct an image $x$ from its encoded latent variable $z$. The $log$ likelyhood term reduces to a simple $L_2$ reconstruction loss, also known as mean square error. It just measures the loss between the reconstructed image and the original image.

The second part of the equation is the KL divergence that measures the distant between two probability distributions. In our case, it measures the distance between $p(z)$ and the normal distribution. While minimizing the loss, $p(z)$ will take shape of the normal distribution as well.

After the training finishes, the latent space should look very closely to the shape of a 2D normal distribution as shown in the image above.

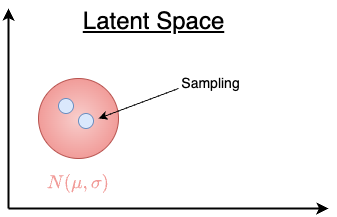

Use VAE to generate images

Once the model is trained, the encoder can encode the images to their latent representation. However, VAE does this a bit differently than the plain Autoencoder. Instead of mapping the input image directly to a single latent vector in the latent space, the VAE encoder converts the input into a group of vectors that follows the Gaussian distribution, namely $\mu$ and $\sigma$. From this latent distribution, we sample points at random, and the decoder converts these sampled points back into the input space. By sampling a random latent vector, we can create a wide variety of new images.

In summary, VAE maintains a compact and smooth latent space, ensuring that most of the points (latent vectors) within the normal distribution in the latent space will lead to plausible samples. Appendix #2 demonstrates how to use VAE in Stable Diffusion 1.5.

Attention U-Net (Conditioning via Cross-Attention)

From the last two sections we know that the CLIP model encodes the prompts into text embeddings in the CLIP space, and the VAE encodes the noise image into latent vectors in the latent space. Since these two lives in different higher dimensional space, how does the text embedding affect the latent vectors? To answer this question, we are going to dive deep into the U-Net architecture.

The traditional U-Net is a U shape architecture commonly used in image semantic segmentation tasks. To support the conditional image generation, Stable Diffusion adds cross-attention modules, which is effective for learning attention-based models of various input modalities.

The U-Net architecture used in Stable Diffusion 1.5 can be found here. At various layers in the encoder path, the latent image features (z) are processed using ResNet blocks and cross-attention blocks. In each cross-attention block:

- The query is the current latent vectors (

[B, HxW, C]) - The key and value come from the CLIP text embeddings (

[B, 77, 768])

Similar to the transformer blocks in LLM, the cross-attention U-Net computes the attention score between image patches (latent vectors) and text embeddings via dot products:

\[\text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}\left( \frac{QK^\top}{\sqrt{d}} \right) V\]This allows each patch in the image (latent vectors) to "look at" what part of the text is most relevant, and pull that information in (e.g., “a red car” → pulls “red” and “car” info to guide denoising).

However, if we look closely, in each Transformer2DModel, we actually have two attention modules - self-attention and cross-attention:

(attn1): Attention(

to_q: Linear(in_features=320, out_features=320, ...)

to_k: Linear(in_features=320, out_features=320, ...)

to_v: Linear(in_features=320, out_features=320, ...)

)

(attn2): Attention(

to_q: Linear(in_features=320, out_features=320, ...)

to_k: Linear(in_features=768, out_features=320, ...) # CLIP text embedding input!

to_v: Linear(in_features=768, out_features=320, ...)

)

- The self-attention module lets the image patches (latent vectors) learn context from its neighbors(similar to LLM ‘s). This is important because it helps generate patches that stay consistent with nearby regions

- The cross-attention module shifts the latent vectors to the desired location in the latent space by attending the text embedding from the input tokens.

Appendix #3 demonstrates the computation process inside attn1 and attn2.

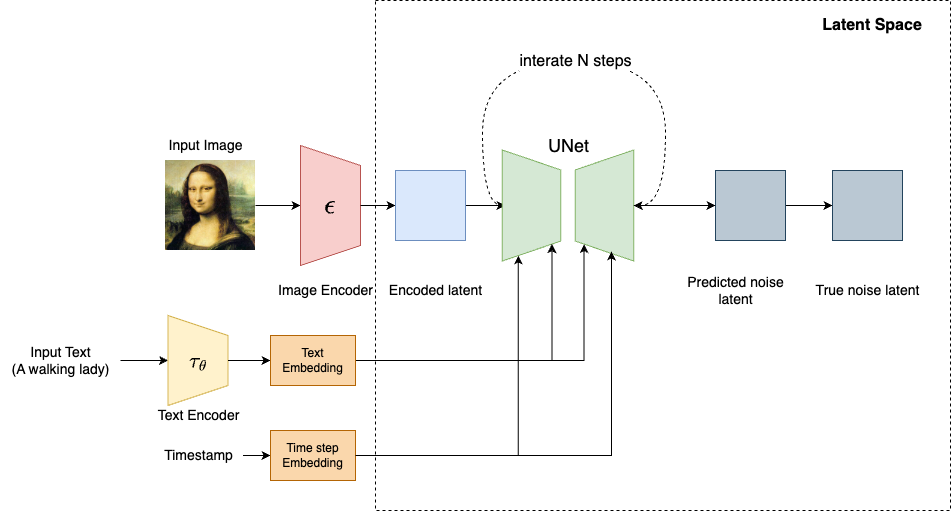

Training the Attention U-Net

Training the attention U-Net model is similar to training the diffusion model outlined in the previous post. The major difference is that we now have (text, image) pairs as our training data.

- Start with an image and caption, e.g. “a cat wearing sunglasses on a beach”

- Convert the image to a latent representation using the VAE encoder →

z₀ - Encode the text prompt using CLIP → text_embedding

- Convert the image to a latent representation using the VAE encoder →

- Add noise to latent

- Sample a time step

tfrom the noise schedule. - Add Gaussian noise to

z₀to getz_tusing the same following formula, Whereεis standard Gaussian noise:

z_t = √α_t * z₀ + √(1 - α_t) * ε - Sample a time step

- Predict the noise with U-Net

- The noisy latent

z_tis passed into the U-Net - The U-Net is conditioned on the text embedding (via cross-attention)

- The U-Net tries to predict the noise

ε_theta

- The noisy latent

-

Compute the loss as follows

L = || ε_theta - ε ||²

Resources

- High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models

- CLIP

- Contrastive Learning

- Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes

- Variational Autoencoders | Generative AI Animated

- Using Stable Diffusion with Python

Appendix #1: CLIP text encoder model architecture

CLIPTextModel(

(text_model): CLIPTextTransformer(

(embeddings): CLIPTextEmbeddings(

(token_embedding): Embedding(49408, 768)

(position_embedding): Embedding(77, 768)

)

(encoder): CLIPEncoder(

(layers): ModuleList(

(0-11): 12 x CLIPEncoderLayer(

(self_attn): CLIPSdpaAttention(

(k_proj): Linear(in_features=768, out_features=768, bias=True)

(v_proj): Linear(in_features=768, out_features=768, bias=True)

(q_proj): Linear(in_features=768, out_features=768, bias=True)

(out_proj): Linear(in_features=768, out_features=768, bias=True)

)

(layer_norm1): LayerNorm((768,), eps=1e-05, elementwise_affine=True)

(mlp): CLIPMLP(

(activation_fn): QuickGELUActivation()

(fc1): Linear(in_features=768, out_features=3072, bias=True)

(fc2): Linear(in_features=3072, out_features=768, bias=True)

)

(layer_norm2): LayerNorm((768,), eps=1e-05, elementwise_affine=True)

)

)

)

(final_layer_norm): LayerNorm((768,), eps=1e-05, elementwise_affine=True)

)

)

Appendix #2: VAE in Stable Diffusion

The VAE architecture used in Stable Diffusion 1.5 can be found here. The following code shows how to use VAE to encode and decode an image:

# Encoding

# the image has to conform to the shape of (N,C,H,W)

print(image.shape) # [1, 3, 300, 300]

vae_model = AutoencoderKL.from_pretrained(

"runwayml/stable-diffusion-v1-5",

subfolder = "vae",

torch_dtype=torch.float16,

cached_dir = CACHE_DIR

)

# encode the image into a laten distribution and sample it randomly

latents = vae_model.encode(image).latent_dist.sample()

print(latents[0].shape) #[4, 37, 37]

# Decoding

with torch.no_grad():

decode_image = vae_model.decode(

latents,

return_dict = False

)[0][0].to("cpu")

# from [-1, 1] to [0, 1]

decode_image = (decode_image / 2 + 0.5).clamp(0, 1)

print(decode_image.shape) # [3, 296, 296]

Let’s first take a look at the encoding process. As mentioned earlier, the output of encoder is a Gaussian distribution. latents = vae_model.encode(image).latent_dist.sample() does three things:

vae_model.encode(image)returns an object that contains a distribution(DiagonalGaussianDistribution) over latent vectors..latent_distis an instance of a Gaussian (Normal) distribution, parameterized by $\mu$ and $\sigma$sample()draws a random sample from this distribution

The DiagonalGaussianDistribution is defined as follows:

class DiagonalGaussianDistribution:

def __init__(self, parameters):

self.mean, self.logvar = torch.chunk(parameters, 2, dim=1)

self.std = torch.exp(0.5 * self.logvar)

def sample(self):

noise = torch.randn_like(self.mean)

return self.mean + self.std * noise

The shape of encoded latent vector is [4, 37, 37]. This is because

4is latent channels (Stable Diffusion uses 4D latent space instead of RGB’s 3)37x37is the spatial resolution (input image was 300x300).

How is 37 calculated?

If we examine the VAE architecture, the output of the encoder in our example from this layer:

(conv_out): Conv2d(512, 8, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(1, 1), padding=(1, 1))

Since we have three conv2d layers in the encoder, each layer does a stride=1 convolution, thus the size of the image shrinks by half after each layer: 300 -> 150 -> 75 -> 37

Let’s say the output of the conv_out layer is a [1, 8, H, W] latent vector, the next thing we do is to split this tensor to two [1, 4, H, W] tensors for $\mu$ and $\sigma$ respectively:

mu, logvar = torch.chunk(tensor, 2, dim=1)

mu # [1, 4, H, W]

logvar #[1,4, H, W]

Then we do the sampling using $\mu$ and $\sigma$:

std = torch.exp(0.5 * logvar) # [1, 4, H, W]

eps = torch.randn_like(std) # [1, 4, H, W]

z = mu + std * eps # [1, 4, H, W]

Finally, z is the latent vector that gets passed to the denoising U-Net.

Appendix #3: Cross Attention U-Net

Below is the architecture of Transformer2DModel, which is heart and soul of the cross-attention U-Net.

(attentions): ModuleList(

(0-1): 2 x Transformer2DModel(

(norm): GroupNorm(32, 320, eps=1e-06, affine=True)

(proj_in): Conv2d(320, 320, kernel_size=(1, 1), stride=(1, 1))

(transformer_blocks): ModuleList(

(0): BasicTransformerBlock(

(norm1): LayerNorm((320,), eps=1e-05, elementwise_affine=True)

(attn1): Attention(

(to_q): Linear(in_features=320, out_features=320, bias=False)

(to_k): Linear(in_features=320, out_features=320, bias=False)

(to_v): Linear(in_features=320, out_features=320, bias=False)

(to_out): ModuleList(

(0): Linear(in_features=320, out_features=320, bias=True)

(1): Dropout(p=0.0, inplace=False)

)

)

(norm2): LayerNorm((320,), eps=1e-05, elementwise_affine=True)

(attn2): Attention(

(to_q): Linear(in_features=320, out_features=320, bias=False)

(to_k): Linear(in_features=768, out_features=320, bias=False)

(to_v): Linear(in_features=768, out_features=320, bias=False)

(to_out): ModuleList(

(0): Linear(in_features=320, out_features=320, bias=True)

(1): Dropout(p=0.0, inplace=False)

)

)

(norm3): LayerNorm((320,), eps=1e-05, elementwise_affine=True)

(ff): FeedForward(

(net): ModuleList(

(0): GEGLU(

(proj): Linear(in_features=320, out_features=2560, bias=True)

)

(1): Dropout(p=0.0, inplace=False)

(2): Linear(in_features=1280, out_features=320, bias=True)

)

)

)

)

(proj_out): Conv2d(320, 320, kernel_size=(1, 1), stride=(1, 1))

)

)

The PyTorch definition of the model lives in diffusers.

Let’s walk through both attn1 (self-attention) and attn2 (cross-attention) for the input tensor - x = [1, 4, H, W]:

- After

conv_in:xbecomes[1, 768, H, W] - After flattening,

xbecomes[1, H*W, 768]

The Self-Attention model is defined as follows(simplified):

class Attention(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

self.to_q = nn.Linear(768, 768, bias=False)

self.to_k = nn.Linear(768, 768, bias=False)

self.to_v = nn.Linear(768, 768 ,bias=False)

self.to_out = nn.Sequential(nn.Linear(768, 768), nn.Dropout(0.0))

def forward(self, x, context=None):

if context is None:

context = x # ← this is self-attention!

q = self.to_q(x) # [B, HW, C]

k = self.to_k(context) # [B, HW, C]

v = self.to_v(context) # [B, HW, C]

scale = q.shape[-1] ** -0.5

sim = torch.matmul(q, k.transpose(-1, -2)) * scale # [B, HW, HW]

attn = torch.softmax(sim, dim=-1)

out = torch.matmul(attn, v) # [B, HW, C]

out = self.to_out(out)

return out

In self-attention,

q,k,vall have the shape[1, HW, 768]attn = softmax(q @ kᵀ / √768)→[1, HW, HW]output = attn @ v→[1, HW, 768]- Reshape back to

[1, 768, H, W]via.permute(0, 2, 1).view(1, 768, H, W)

The Cross-Attention model is defined as follows(simplified):

class Attention(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

self.to_q = nn.Linear(768, 768, bias=False)

self.to_k = nn.Linear(768, 320, bias=False)

self.to_v = nn.Linear(768, 320 ,bias=False)

self.to_out = nn.Sequential(nn.Linear(768, 768), nn.Dropout(0.0))

def forward(self, x, text_embed, mask=None):

# Project queries from image features

q = self.to_q(x) # shape: [B, HW, C]

# Project keys and values from text_embed

k = self.to_k(text_embed) # [B, T_text, C]

v = self.to_v(text_embed) # [B, T_text, C]

# Scaled dot-product attention

scale = q.shape[-1] ** -0.5

sim = torch.matmul(q, k.transpose(-1, -2)) * scale # [B, HW, T_text]

if mask is not None:

sim = sim.masked_fill(mask, -float("inf"))

attn = torch.softmax(sim, dim=-1) # attention weights

out = torch.matmul(attn, v) # [B, HW, C]

out = self.to_out(out) # final projection

return out

Continuing from attn1,

- The input latent vector has shape:

[1, 768, H, W]→ flattened to[1, HW, 768] - Text embedding (CLIP) has shape:

[1, N, 768](N tokens, N <= 77) q = to_q(x)→[1, HW, 768]from the image latent, whereHW = H × W (e.g. 37×37 = 1369)k = to_k(text_embed)→[1, N, 768]from the text embeddings, projected to match inner dimensionv = to_v(text_embed)→[1, N, 768]also from the text embeddingsattn = softmax(q @ kᵀ / √768)→[1, HW, N]Each image patch (query) attends over N tokens (text prompt length)output = attn @ v→[1, HW, 768]Injects textual semantic information into each image patch- Reshape back to

[1, 768, H, W]via:.permute(0, 2, 1).view(1, 768, H, W)